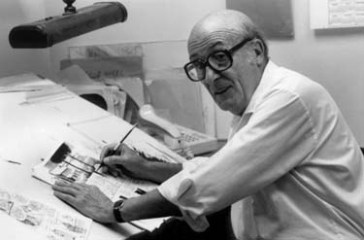

Will Eisner (1917-2005) would have been about twelve years old when Tintin first appeared, and, like Hergé, Eisner’s contribution to the world of comics is immeasurable and invaluable. Eisner’s status as a comic book artist is such that each year the Eisner Award is presented in recognition of significant achievement in this particular medium. Eisner’s stories usually feature city-based people struggling with poverty and hardship: often the ending is an unhappy one, but the tales themselves are rarely sentimental. Eisner’s characters have been brought low and made mean by hunger and hardship and there is a hardened edge to many of them, but one would have to be stony-hearted indeed not to sympathise. Eisner writes about those who lose everything during the Great Depression, those who struggle to raise a family in an impoverished and often violent neighbourhood, those who are the victims of racism, antisemitism, domestic abuse, those who are born poor and die even poorer. And after reading Eisner, one is left with a strong sense of the warmth and sympathy he felt towards his creations, how much he understood human nature and the desperate fight for survival.

Eisner is, after all, writing from his own life. His parents were poor immigrants to the US and his father, also an artist, had a hard time making ends meet. Eisner was born in Brooklyn and his childhood in New York was a difficult one. He shared those experiences in his heartfelt and beautifully drawn graphic novels; he also wrote books of instruction on sequential art and lectured at the School of Visual Arts in New York City. There’s a bibliography at the end of this post and you can read more about Will Eisner on his Wikipedia page here.

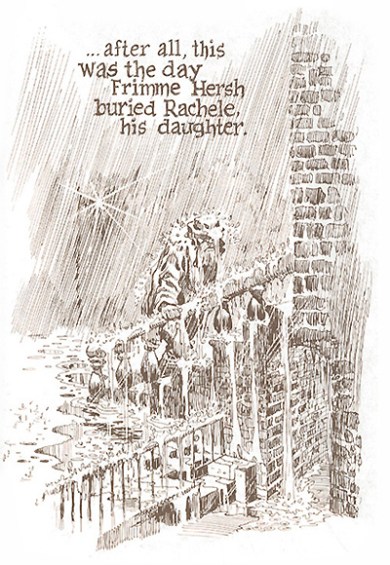

One thing about Eisner is that he does ‘weather’ better than anyone else I’ve come across so far. Look at this from The Contract With God:

The torrential downpour mirrors and magnifies the tears of Frimme Hershe, who is returning from burying his daughter, Rachele, the fictional counterpart of Eisner’s own daughter, Alice, who died of leukaemia when she was a teenager. Overwhelmed by grief, Hershe breaks his contract with God and becomes a ruthless landlord, but he never loses our sympathy because we have seen what he once was and we know what shape his demons take.

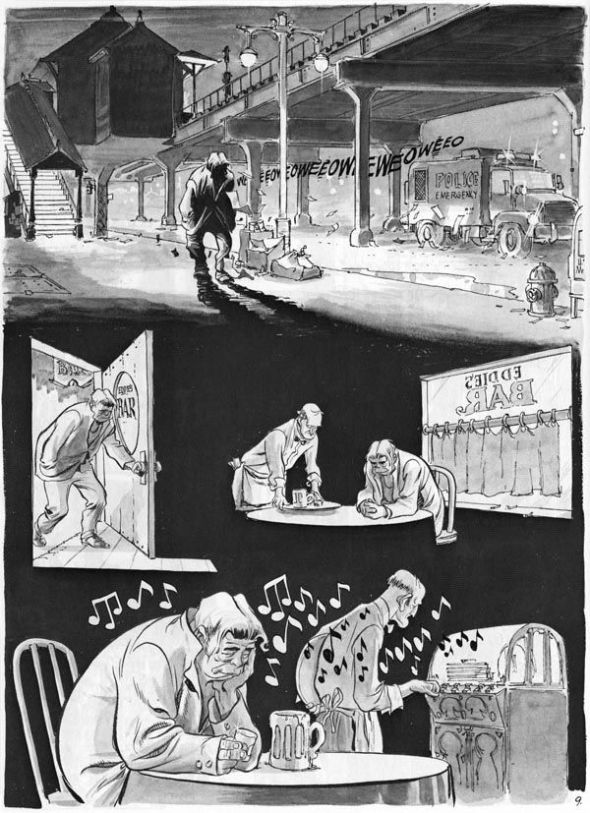

Eisner draws beautiful snow as well. In his story Sanctum, poor Pincus Pleatnik believes there to be safety in anonymity and he spends his life trying to keep out of everyone’s way. When his death is reported in error in the obituaries, events catch up with Pincus in quick succession, and, locked out of his home, he is forced to spend the night sleeping in the snow in one of the city’s parks. Unable to contact anyone to verify his continued existence and unrecognised by most owing to his habit of avoiding human contact, Pincus eventually meets his death when he attempts to escape from the union thugs who have kidnapped him, but who didn’t intend to harm him. It’s a very sad story and the salt in the wound comes at the end when the editor whose report led indirectly to Pincus’ death is awarded an ‘errorless editor medal…and a $5000 bond’ on her retirement. I actually jabbed the page and yelled ‘He’s dead because of you!’ Eisner elicits an emotional response from the reader through use of irony as here in the story of Pincus, or through jarring juxtapositions such as those in the scene below: the man trudging through the streets and drinking in the bar is pursued throughout by the notes of a jolly tune, but when we see him here he is returning from the hospital where he has seen his wife’s body. She is beyond the help of the ambulance which rushes past her husband at the top of the picture, the siren temporarily taking the place of the string of musical notes.

I’m sorry this post is such a sad one, but this is why I like Eisner’s work so much. Sometimes there’s nothing like having a good blub, and I have shed many a tear over Eisner’s tales. And in fact, I’ve saved the saddest for last. Ernest Hemingway was once challenged to write a short story in six words that would make everyone cry…and Eisner illustrated it, as seen here below. Those of you who’ve spent a long time on your eye make-up today might want to look away now unless you want to be reapplying your mascara very shortly…

The story Hemingway wrote was ‘For sale, baby shoes, never used’, and Eisner has in fact added one more word to this story by labelling the pawn shop, just in case anyone missed the three-ball symbol in the corner. What is so heartrendingly awful about this brief strip is the woman’s broken and defeated gait as she enters the shop, carrying her box containing the baby shoes. Her beaten-down posture is the same when she exits the shop holding the cash she received in exchange. I’ve turned down the corner of this page in my book so I can skip over it more easily: the sight of that poor woman doubled over with grief is too much for me and mascara is too expensive to have to be applying it more than once a day.

Dry your tears now and remind yourself that this is only a story…

Coming soon! – My Top Five Favourite Comic Books: The Also-Rans and an Outsider

Bibliography:

(All titles by Will Eisner)

- New York: Life in the Big City

- The Contract with God Trilogy

- Graphic Storytelling and Visual Narrative

- Expressive Anatomy for Comics and Narrative

- Comics and Sequential Art