I haven’t forgotten about the 2016 Reading Challenge – I just haven’t been very diligent about writing it up. Truth be told, though, I’m behind with the reading, and given that it’s mid-November, I think this is going to turn into a challenge for next year as well as this one, but THAT’S OKAY and I’m not going to beat myself up about it BECAUSE it occurred to me last week when I was attending a conference at Sheffield Hallam that I’ve done very little reading this year outside the confines of my MA course. I read all the time, but I’m reading books about books rather than just books (if you see what I mean). For example, at present I’m reading John Guillory’s Cultural Capital because I have a unit coming up which focuses on the literary canon. It’s an interesting but difficult book: I’m reading at frustration level a lot of the time, but I understand just about enough to persevere with it. It is a shame, though, that studying for a literary-linguistic degree means I’m struggling to make time for a bit of the actual reading-for-pleasure. Trouble is that when I want to relax, reading isn’t my activity of choice right now: I’ve been reading all day, I say to myself, and now all I want to do is listen to that Pink Martini CD and paint pots.

So, this is a sort of cheat of a blog post because actually I’m just going to recap where I’ve got to with the reading challenge and list all the stuff I still have to read.

Okay. So. The image above lists the twelve categories for the challenge. I’ve already written about A Book Published Before You Were Born and A Book You Can Read In A Day, but that’s as far as I’ve got. I’m waiting until the end of the year until I make my choice for A Book Published This Year, but I’ve chosen titles for all the other categories and I’ve listed these with notes below.

A Book You’ve Been Meaning To Read

Well, actually, I haven’t decided this one. But my bookshelves are full of books that I’ve been meaning to read, so I could put LITERALLY ANYTHING here and it wouldn’t make any difference.

A Book Recommended By Your Local Librarian Or Bookseller

The Chimes by Anna Smaill. Yes, I have a copy. No, I haven’t read it yet.

A Book You Should Have Read In School

The Turn of the Screw by Henry James. I also have to read The Ambassadors for my course, so 2016 is clearly my year for reading Henry James. Plus, see below…

A Book Chosen For You By Your (etc.)

The etc. denotes that I roundly rejected the book chosen for me by my sibling, which was A A Gill’s Pour Me: A Life (sorry Tif) and have chosen instead a book recommended by a friend. I just couldn’t get on with Gill. I found his overwritten and self-indulgent prose quite nauseating, and then I read somewhere that he murdered a baboon just to find out what it was like to kill. Gill is in the news this morning because he’s announced that he has cancer, but I don’t care. My sympathy lies with that poor baboon. For this category, I’ve chosen instead The Spoils of Poynton by Henry James, and I have read this and I ENJOYED IT! I’ve been meaning to write a post about Spoils and ekphrasis, but, you know…it’s coming. It’s coming.

A Book That Was Banned At Some Point

Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll. My Significant Other is always nagging me about not having read this. It is (apparently) an unacceptable gap in my knowledge. Okay, fine, I’ll read it. I’ve bought a copy. I haven’t read it yet.

In case you’re wondering why it was banned, the Wikipedia page for banned books tells us that Alice was

Formerly banned in the province of Hunan, China, beginning in 1931, for its portrayal of anthropomorphized animals acting on the same level of complexity as human beings. The censor General Ho Chien believed that attributing human language to animals was an insult to humans. He feared that the book would teach children to regard humans and animals on the same level, which would be “disastrous”.

A A Gill would probably agree with General Ho Chien’s sentiments, but I don’t, and I suspect that baboon didn’t either. Oh, and by the way Ho Chien! Your name is French for dog.

A Book You Previously Abandoned

Oh god. This is Nabokov’s Pnin. I started it – and it is wonderful – but I’m a very anxious person and this book is an absolute nightmare for those of us who worry all the time about journeys going wrong, things getting lost, important stuff getting left behind, etc. This book is like all my anxiety nightmares rolled into one big fat sweaty never-ending anxiety horror film.

A Book You Own But Have Never Read

I’ve done this one! I read The Woman in White by Wilkie Collins and it was bloody awful. It helped me remember why I avoid nineteenth-century fiction. Proper blog post to follow. In due course.

A Book That Intimidates You

Ah, now, I’m going to have a go at House of Leaves by Mark Z. Danielewski. I’ve never read anything like this before, plus it’s HUGE. But given the way my literary interests are leaning these days, I think this is a must-read.

(What’s the Z for? Is it for real or is it a pose?)

A Book You’ve Already Read At Least Once

I could cheat with this one because I had to re-read Titus Andronicus as part of my course, but I’m going to stick with my original choice of Cold Comfort Farm by Stella Gibbons, just because Gibbons’ book is enormous fun. I’m saving this one for the Christmas holiday.

Ta-dah! All my procrastinatory effort laid out before you in block quotes. There’ll be more to follow. I’ll get back to you on this.

I’m kicking off this year’s

I’m kicking off this year’s

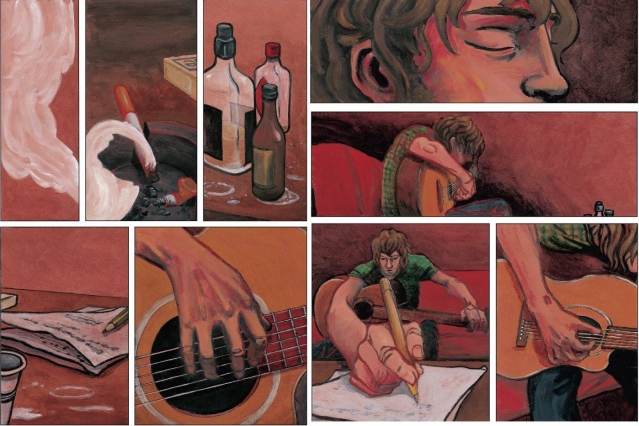

d, the microphone) that Tazane is onstage singing, but we can guess from the spiky balloons and large spaced-out font of the letters that he is not crooning softly, but belting out the words. The colour scheme reinforces this impression: think how these panels would differ if rendered in pale blue or green, for example.

d, the microphone) that Tazane is onstage singing, but we can guess from the spiky balloons and large spaced-out font of the letters that he is not crooning softly, but belting out the words. The colour scheme reinforces this impression: think how these panels would differ if rendered in pale blue or green, for example.