The account of his [Wickham’s] connection with the Pemberley family, was exactly what he had related himself; and the kindness of the late Mr. Darcy, though she had not before known its extent, agreed equally well with his own words. So far each recital confirmed the other: but when she came to the will, the difference was great. What Wickham had said of the living was fresh in her memory, and as she recalled his very words, it was impossible not to feel that there was gross duplicity on one side or the other; and, for a few moments, she flattered herself that her wishes did not err. But when she read, and re-read with the closest attention, the particulars immediately following of Wickham’s resigning all pretensions to the living, of his receiving in lieu, so considerable a sum as three thousand pounds, again was she forced to hesitate. She put down the letter, weighed every circumstance with what she meant to be impartiality – deliberated on the probability of each statement – but with little success. On both sides it was only assertion. Again she read on. But every line proved more clearly that the affair, which she had believed it impossible that any contrivance could so represent, as to render Mr. Darcy’s conduct in it less than infamous, was capable of a turn which must make him entirely blameless throughout the whole.

Jane Austen ‘Pride and Prejudice’ Oxford World’s Classics edition (1990) p. 182

This passage represents a turning point in the narrative: first Darcy and then Elizabeth are forced to reassess their own embedded narratives (Palmer, 2004) in order to incorporate that of the other. Darcy has spent much of the night writing an explanatory letter to Elizabeth after she has given her reasons for refusing his proposal of marriage, and the excerpt under discussion shows Elizabeth’s reaction on reading this letter and learning a different sort of truth to the one she has previously upheld. The world-view of each character alters dramatically, and this change is reflected also in the situation of the reader, who is forced to revisit and reassess the novel’s events up to this point at the same time Elizabeth does so, and is therefore subject to the same reading experience as Elizabeth. Many of Elizabeth’s memories will tally with the reader’s recollection of events, and the reader, alongside Elizabeth, will revise formerly-created contextual frames (Emmott, 1997). It is now that the reader will realise that many of these memories were not, in fact, impartially formed, but were coloured by Elizabeth’s perception of events. She is the novel’s focaliser, and at this point she is also the focalised while she examines her recollections and even her conscience: this passage occurs shortly before Elizabeth famously cries out: ‘Till this moment, I never knew myself’ (185). It is at this moment in the novel that the difference between the narrator and focaliser is apparent, and once this difference is recognised, the reader is also cognisant of the extent to which the two were previously confused. The narrator has encouraged the deception of the reader through discreet use of the focaliser-character’s world-view to distort the creation of memory as the novel’s events occurred, thus enabling the narrator to administer a salutary corrective to both Elizabeth and the reader when Darcy’s letter is read and the ugly truth about Wickham’s character known.

The narrator states that Elizabeth has to collect herself before re-reading the letter, an activity described as a ‘mortifying perusal of all that related to Wickham’ (182). Although Darcy is not yet exonerated for his part in Bingley’s rejection of Jane, the narrator indicates here that he is in no way to be held accountable for Wickham’s misfortunes, and that Elizabeth knows this to be the case even before she embarks upon reading the letter for a second time. In writing the letter, Darcy has provided his own defence against Wickham’s aspersions, and Elizabeth is to judge between the two narratives. The passage under consideration shows Elizabeth weighing the evidence before passing judgement. Sections of Darcy’s letter reappear in paraphrase: for example, ‘Wickham’s resigning all pretensions to the living, of his receiving in lieu, so considerable a sum as three thousand pounds’; thus the reader receives the same information twice in quick succession having read Darcy’s letter in the chapter preceding, and these reiterations now serve as a makeshift summing-up. In addition, these paraphrases are iconic of Elizabeth’s own experience of re-reading Darcy’s words, as she also repeatedly encounters the same information in her several attempts to digest the contents of the letter.

The written form of the chosen passage also mirrors the meaning in a more immediate sense. Vocabulary choices reflect both language of a legal character, and the act of comparing two differing accounts of the same events and weighing or measuring one account against the other: exactly, equally, confirmed, difference, on one side or the other, read and re-read, put down, weighed, deliberated, probability, each statement, both, assertion, every line proved, impossible, represent, entirely, the whole. On a syntactical level, Elizabeth’s mental gymnastics are encapsulated in the way in which her initial thoughts are each time balanced against another statement introduced with the co-ordinating conjunction ‘but’, which appears four times in this short excerpt. The ‘written’ nature of the passage reveals to the reader the presence of a narrator beyond Elizabeth’s consciousness, and if this were not enough, the narrator’s voice actively intrudes three times to make it clear to the reader that Elizabeth is mentally fighting against the information newly-received, and in the process is doing her best to retain her former mind-set: ‘for a few moments, she flattered herself that her wishes did not err’; ‘weighed every circumstance with what she meant to be impartiality’; and thirdly, the twisty final line of the passage contains a subordinate clause which comprises 23 words – exactly the same number as the main clause. Darcy is found to be ‘blameless’ in the more important main clause, but the lengthy subordinate clause represents the depth and rigidity of the opinion Elizabeth had willingly formed beforehand. She finds her previous opinion difficult to relinquish, as demonstrated here in the syntax of subordinate clause (former beliefs) versus main clause (new beliefs). While Elizabeth struggles hard to exonerate Wickham, in the end she cannot do so, and is therefore confronted not only with the downfall and disgrace of her former favourite, but also the humiliating knowledge that she herself has judged wrongly and has allowed her prejudice to blind her to the reality of the situation: ‘Pleased with the preference of one, and offended by the neglect of the other, on the very beginning of our acquaintance, I have courted prepossession and ignorance, and driven reason away, where either were concerned’ (185). Elizabeth now joins the narrator in balancing her words: pleased/offended; preference/neglect; ignorance/reason.

Until this moment, the narrator has colluded with the focaliser-character to mislead the reader, and now the narrator takes a step back to uncover the deception. Elizabeth’s desire for Wickham to be innocent is clearly acknowledged by the narrator, tied as this circumstance is to Elizabeth’s self-respect, and her partiality is revealed. In staying close to Elizabeth, the narrator has before this moment presented her views as if they were the objective truth, but in retrospect, both the reader and Elizabeth can see that her emotional response at the time of previous meetings with the two men was instrumental in the formation of her memory of each event (Wiltshire, 2014). Darcy’s revelations force Elizabeth to confront the folly of her behaviour and she says in conversation with Jane: ‘ “the misfortune of speaking with bitterness, is a most natural consequence of the prejudices I had been encouraging” ’ (200). In accepting without question Elizabeth’s view of Darcy and Wickham before Darcy writes his letter, the reader has also been hoodwinked and is complicit in Elizabeth’s shame. Austen’s narrator is one who deceives in order to instruct, a very different approach to the didactic satirical method adopted by Swift in Gulliver’s Travels. Austen chooses to involve the reader instead of actively preaching and the linear character of the reading experience is very much taken into account by Austen’s wily narrator. Austen is well-known as an accomplished exponent of free indirect discourse, and it is through liberal use of such that voices of narrator, focaliser and character become intermingled and indistinguishable; thus when the rebuke comes for Elizabeth Bennet and Emma Woodhouse, the reader feels it just as keenly. Re-reading Austen is a very different experience to an initial reading of her novels because one can only be fooled by the likes of George Wickham and Frank Churchill once. The pleasure in re-reading is in retracing exactly how the deception was carried out.

In terms of the story, this is a moment when nothing is happening. Elizabeth is merely reading and re-reading Darcy’s letter while remembering and reassessing former events. Genette would refer to this as a pause in the story (1980), but this is not to say that the same is true of the narrative: in actual fact, there is an enormous amount of mental activity happening at this point which will determine how future events play themselves out. It is, as previously stated, a pivotal moment in the narrative. Elizabeth is made aware of her error and from this point onwards she begins to fall in love with Darcy. In Proppian terms, this is the moment when the hero is recognised and the false hero or villain exposed (Toolan, 2001: 19-20).

It is notable also that Elizabeth’s mental activity at this crucial juncture is linked to one of the much wider themes of the novel. Wiltshire argues that Pride and Prejudice is a novel about memory and how memories are created (2014: 51-71), and the whole of chapter thirteen of Austen’s novel, from which this extract is taken, is given over to Elizabeth’s musings on reading the letter. Elizabeth examines her memory of events and makes several corrections in the light of what she now knows. The reader is not strictly witnessing flashbacks, but the narrator actively points the reader to previous episodes where Elizabeth interprets events according to the background context entertained at the time, which leads to the creation of a memory coloured by an emotional response: the relevant parts of the text are ‘was exactly what he had related himself’; and ‘agreed equally well with his own words’; but then the vital difference emerges in relation to Darcy’s father’s will and ‘What Wickham had said of the living’.

List of references:

Austen, J. (1990 [1813]) Pride and Prejudice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Emmott, C. (1997) Narrative Comprehension: A Discourse Perspective. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Genette, G. (1980) Narrative Discourse: An Essay in Method. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Palmer, A. (2004) Fictional Minds. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Swift, J. (1967 [1726]) Gulliver’s Travels. J. Chalker & P. Dixon. Eds. London: Penguin.

Toolan, M. (2001) Narrative: A Critical Linguistic Introduction. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

Wiltshire, J. (2014) The Hidden Jane Austen. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

I’m kicking off this year’s

I’m kicking off this year’s

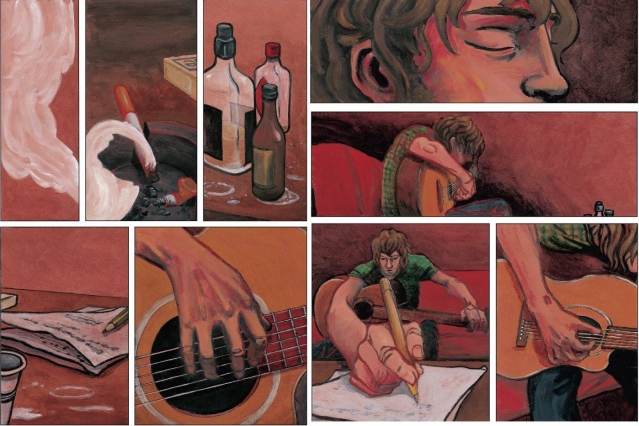

d, the microphone) that Tazane is onstage singing, but we can guess from the spiky balloons and large spaced-out font of the letters that he is not crooning softly, but belting out the words. The colour scheme reinforces this impression: think how these panels would differ if rendered in pale blue or green, for example.

d, the microphone) that Tazane is onstage singing, but we can guess from the spiky balloons and large spaced-out font of the letters that he is not crooning softly, but belting out the words. The colour scheme reinforces this impression: think how these panels would differ if rendered in pale blue or green, for example.