There are a multiplicity of voices in The Waste Land at any one time, which I have attempted to categorise below. The poem is informed by various religious and mythical texts: The Bible, the Buddha’s Fire Sermon, The Upanishads, Sybil and Tiresias from Greek and Roman texts, and, perhaps most important of all, the Grail Legend. Eliot makes numerous references to other literary texts; this category includes the self-referentiality of the poem itself in its various repetitions and parallelisms, and of course, Eliot’s own poetry (The Death of Saint Narcissus, the Sweeney poems, Dans le Restaurant). The poem features voices from the contemporary scene in its references to WWI, and, notably, songs from music-hall routines and American ragtime. There is birdsong from the nightingale, the hermit-thrush, a French cockerel, and the gulls of Part IV. There are voices from actual people now dead: Marie Larisch, ‘Mr Eugenides’ (whose proposition to Eliot in Part III was real), and Ellen Kellond, the Eliots’ housemaid, provided material for the scene in the public house. It has been suggested that Eliot himself and his first wife provide the voices in lines 111-138 (Southam, 1968: 160). There are the lines spoken by the characters of the poem, many of whom are imported from other literary texts and bring with them the voices from their original provenance. In addition to all this, there are numerous inarticulate speech-acts in which it is known that a speech act occurs, but the words themselves are unknown: chatter from the fish market, whispers, shouting and crying, ‘maternal lamentation’, voices from cisterns and wells, and this category can be stretched to include the ‘[s]ighs, short and infrequent’. The incessant noise of the cricket or the cicada is balanced against instances of the absence of sound: ‘the frosty silence in the gardens’ or the dry stone over which no water flows.

There are a multiplicity of voices in The Waste Land at any one time, which I have attempted to categorise below. The poem is informed by various religious and mythical texts: The Bible, the Buddha’s Fire Sermon, The Upanishads, Sybil and Tiresias from Greek and Roman texts, and, perhaps most important of all, the Grail Legend. Eliot makes numerous references to other literary texts; this category includes the self-referentiality of the poem itself in its various repetitions and parallelisms, and of course, Eliot’s own poetry (The Death of Saint Narcissus, the Sweeney poems, Dans le Restaurant). The poem features voices from the contemporary scene in its references to WWI, and, notably, songs from music-hall routines and American ragtime. There is birdsong from the nightingale, the hermit-thrush, a French cockerel, and the gulls of Part IV. There are voices from actual people now dead: Marie Larisch, ‘Mr Eugenides’ (whose proposition to Eliot in Part III was real), and Ellen Kellond, the Eliots’ housemaid, provided material for the scene in the public house. It has been suggested that Eliot himself and his first wife provide the voices in lines 111-138 (Southam, 1968: 160). There are the lines spoken by the characters of the poem, many of whom are imported from other literary texts and bring with them the voices from their original provenance. In addition to all this, there are numerous inarticulate speech-acts in which it is known that a speech act occurs, but the words themselves are unknown: chatter from the fish market, whispers, shouting and crying, ‘maternal lamentation’, voices from cisterns and wells, and this category can be stretched to include the ‘[s]ighs, short and infrequent’. The incessant noise of the cricket or the cicada is balanced against instances of the absence of sound: ‘the frosty silence in the gardens’ or the dry stone over which no water flows.

Given this cacophony of voices, to identify a single protagonist as Edmund Wilson tries to do is to attempt to impose a level of coherence on the poem that it arguably does not have. Wilson’s efforts to single out a voice and construct a narrative sequence ending in the death of the ‘hero’ are, finally, unconvincing (Wilson, 1922). He wants a story with a beginning and an end – rather like a quest, such as the search for the Grail – but the fragmentary nature of the poem coupled with its frequent instances of repetition renders the whole more like a frozen moment in which all time is suspended. The presence of prophetic figures such as the Sybil and Tiresias, plus the fake fortune-teller Madame Sosostris, lends some weight to this reading.

Given this cacophony of voices, to identify a single protagonist as Edmund Wilson tries to do is to attempt to impose a level of coherence on the poem that it arguably does not have. Wilson’s efforts to single out a voice and construct a narrative sequence ending in the death of the ‘hero’ are, finally, unconvincing (Wilson, 1922). He wants a story with a beginning and an end – rather like a quest, such as the search for the Grail – but the fragmentary nature of the poem coupled with its frequent instances of repetition renders the whole more like a frozen moment in which all time is suspended. The presence of prophetic figures such as the Sybil and Tiresias, plus the fake fortune-teller Madame Sosostris, lends some weight to this reading.

The literary references of The Waste Land operate a two-way effect in which the works alluded to infiltrate and resonate throughout Eliot’s lines; simultaneously, Eliot’s reformulation of literary fragments invites a re-evaluation of the original texts. This is entirely consistent with the logic of Eliot’s argument in his essay ’Tradition and the Individual Talent’, in that a new work of art stems from that which has gone before and, in being assimilated into the existing body of literature, affects how pre-existing works are perceived. This process can be exemplified through discussion of Eliot’s borrowing of Enobarbus’ words to describe Cleopatra: Eliot changes only three words of the first line and a half of Enobarbus’ speech, thus the reference is unmistakable. The domineering character of Cleopatra is transported into Eliot’s lines which, in their turn, emphasise the element of voyeurism inherent in the scene and question the nature of the relationship between art and artifice.

The literary references of The Waste Land operate a two-way effect in which the works alluded to infiltrate and resonate throughout Eliot’s lines; simultaneously, Eliot’s reformulation of literary fragments invites a re-evaluation of the original texts. This is entirely consistent with the logic of Eliot’s argument in his essay ’Tradition and the Individual Talent’, in that a new work of art stems from that which has gone before and, in being assimilated into the existing body of literature, affects how pre-existing works are perceived. This process can be exemplified through discussion of Eliot’s borrowing of Enobarbus’ words to describe Cleopatra: Eliot changes only three words of the first line and a half of Enobarbus’ speech, thus the reference is unmistakable. The domineering character of Cleopatra is transported into Eliot’s lines which, in their turn, emphasise the element of voyeurism inherent in the scene and question the nature of the relationship between art and artifice.

Eliot replaces Shakespeare’s ‘pretty dimpled boys’ with two ‘golden Cupidon[s]’, one of which is peeping and the other covers his eyes. The world clamours to get a glimpse of Cleopatra while Eliot’s Cupidons are not looking or not supposed to see. The crude sexual reference in ‘Jug Jug’ heard by ‘dirty ears’ underscores further the voyeuristic nature of the scene, and this theme is reworked in Part III when Tiresias foresees and vicariously participates in the sex act between the ‘young man carbuncular’ and the tired typist.

The living boys are substituted for statues and Eliot’s description of them is therefore ekphrastic, as indeed, is this whole section of the poem from lines 77-106. Shakespeare’s Cleopatra is herself reckoned to be even more beautiful than an artistic depiction of Venus which flatters the goddess. The comparison of art and artifice continues in the description of the artificial fragrances which feature heavily in the scene: Eliot’s perfumes are cloying and ‘synthetic’, producing a disorienting, narcotic effect which renders the senses ‘troubled, confused’, particularly when coupled with the refracted light from the many doubled reflections of candle-flames and jewels; similarly, the perfumes emanating from Cleopatra’s barge have an intoxicating effect not only on the humans present, but also on the wind itself. Enobarbus’ eloquent admiration of Cleopatra is unusually expressive for such a moderate character as he; Eliot’s re-working of the speech invites the possibility that Enobarbus is purposely drawing attention to the deliberately staged quality of Cleopatra’s famous entrance.

The living boys are substituted for statues and Eliot’s description of them is therefore ekphrastic, as indeed, is this whole section of the poem from lines 77-106. Shakespeare’s Cleopatra is herself reckoned to be even more beautiful than an artistic depiction of Venus which flatters the goddess. The comparison of art and artifice continues in the description of the artificial fragrances which feature heavily in the scene: Eliot’s perfumes are cloying and ‘synthetic’, producing a disorienting, narcotic effect which renders the senses ‘troubled, confused’, particularly when coupled with the refracted light from the many doubled reflections of candle-flames and jewels; similarly, the perfumes emanating from Cleopatra’s barge have an intoxicating effect not only on the humans present, but also on the wind itself. Enobarbus’ eloquent admiration of Cleopatra is unusually expressive for such a moderate character as he; Eliot’s re-working of the speech invites the possibility that Enobarbus is purposely drawing attention to the deliberately staged quality of Cleopatra’s famous entrance.

The Cleopatra equivalent herself, however, is not described in the parallel scene in The Waste Land. Instead, the focus switches to a painting displayed ‘[a]bove the antique mantel’ depicting Ovid’s story of the rape, mutilation and transformation of Philomela. The figure of Philomela features twice in Eliot’s poem at lines 99-103 and again in 203-206, the latter being a reference to Trico’s song in Lyly’s Campapse (Southam, 1968: 159). Philomela functions in the poem as an expression of the themes of sex and voyeurism. In Ovid’s story, Tereus mentally rapes Philomela before physically forcing himself upon her: ‘his mind’s eye shaped, / To suit his fancy, charms he’d not yet seen’ (Ovid, 1986: 136), both acts being witnessed also by the reader. Sex in The Waste Land is unsatisfactory, a duty or something to be endured (Lil and the typist), a profession (Mrs Porter and her daughter), or an act performed at the weekend with a stranger (Mr Eugenides). It is also barren and non-productive: Lil takes pills to induce a miscarriage in ‘A Game of Chess’, and in the Philomela story, the two sisters murder Itys, Procne’s son by Tereus, as an act of revenge. Eliot’s second reference to Philomela occurs immediately after the lines containing references to Eliot’s own Sweeney poems, a polite version of a bawdy WWI ballad (Southam, 1968: 168) and Paul Verlaine’s Parsifal. Sweeney appears here in his sexual character (’Sweeney Erect’), subject to the lust the Buddha preaches against in the Fire Sermon; Mrs Porter and her daughter are ‘notorious among Australian troops for passing on venereal disease’ (Southam, 1968: 168); Parsifal resists the temptation to sleep with the beautiful maidens put in his path and gains the Holy Spear with which he cures Amfortas, the Wounded King, who was seduced by Kundry and in consequence cursed with a wound that would not heal. Sex features in Eliot’s poem in terms of the violence of men, the seductive powers of women, and the danger of contracting disease through sexual contact; the rewards available to those who stay pure are encapsulated in the reference to Parsifal. In the wider context of the whole poem and the Grail legend which informs it, sex is at the heart of the misery experienced by the land and its inhabitants, all now laid to waste.

The Cleopatra equivalent herself, however, is not described in the parallel scene in The Waste Land. Instead, the focus switches to a painting displayed ‘[a]bove the antique mantel’ depicting Ovid’s story of the rape, mutilation and transformation of Philomela. The figure of Philomela features twice in Eliot’s poem at lines 99-103 and again in 203-206, the latter being a reference to Trico’s song in Lyly’s Campapse (Southam, 1968: 159). Philomela functions in the poem as an expression of the themes of sex and voyeurism. In Ovid’s story, Tereus mentally rapes Philomela before physically forcing himself upon her: ‘his mind’s eye shaped, / To suit his fancy, charms he’d not yet seen’ (Ovid, 1986: 136), both acts being witnessed also by the reader. Sex in The Waste Land is unsatisfactory, a duty or something to be endured (Lil and the typist), a profession (Mrs Porter and her daughter), or an act performed at the weekend with a stranger (Mr Eugenides). It is also barren and non-productive: Lil takes pills to induce a miscarriage in ‘A Game of Chess’, and in the Philomela story, the two sisters murder Itys, Procne’s son by Tereus, as an act of revenge. Eliot’s second reference to Philomela occurs immediately after the lines containing references to Eliot’s own Sweeney poems, a polite version of a bawdy WWI ballad (Southam, 1968: 168) and Paul Verlaine’s Parsifal. Sweeney appears here in his sexual character (’Sweeney Erect’), subject to the lust the Buddha preaches against in the Fire Sermon; Mrs Porter and her daughter are ‘notorious among Australian troops for passing on venereal disease’ (Southam, 1968: 168); Parsifal resists the temptation to sleep with the beautiful maidens put in his path and gains the Holy Spear with which he cures Amfortas, the Wounded King, who was seduced by Kundry and in consequence cursed with a wound that would not heal. Sex features in Eliot’s poem in terms of the violence of men, the seductive powers of women, and the danger of contracting disease through sexual contact; the rewards available to those who stay pure are encapsulated in the reference to Parsifal. In the wider context of the whole poem and the Grail legend which informs it, sex is at the heart of the misery experienced by the land and its inhabitants, all now laid to waste.

List of references

Eliot, T.S. (1940) The Waste Land and other poems. London: Faber and Faber.

Eliot, T.S. (1920) Tradition and the Individual Talent. The Sacred Wood: Essays on poetry and criticism. 42–53. Available at: https://archive.org/details/sacredwoodessays00eliorich [Accessed January 2, 2017].

Everett, D. (2015) Paul Verlaine’s Poem ‘Parsifal.’ Monsalvat: the Parsifal home page. Available at: http://www.monsalvat.no/verlaine.htm [Accessed January 16, 2017].

Ovid (1986) Metamorphoses. E. J. Kenney (ed). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Shakespeare, W. (1954) Antony and Cleopatra. M. R. Ridley (ed). London: Routledge.

Southam, B.C. (1968) A Student’s Guide to the Selected Poems of T. S. Eliot. 6th ed. London: Faber and Faber.

Wilson, E. (1922) The Poetry of Drouth. The Dial. 73: 611–616.

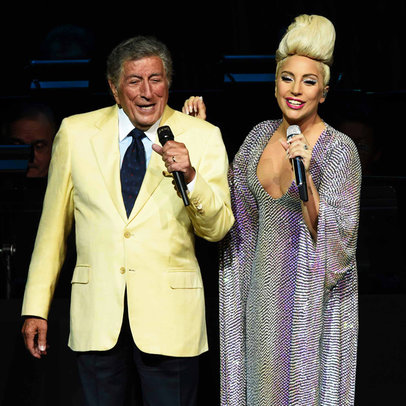

The performance, therefore, is a ‘good’ one because it evoked past times. It is compared with present-day concerts in order to voice an unfavourable opinion of the modern-day lack of rapport between artists sharing a stage, and the concert is evaluated through the rapport between the performers involved, the audience reaction and the quality of the vocal performances. The material performed is listed without comment, with the implication that its superior standard is a given. The performance is treated as entertainment, with (for example) its descriptions of the banter between the performers, but the music performed clearly has a status approaching that of high art due in part to its continuing appeal and existing longevity.

The performance, therefore, is a ‘good’ one because it evoked past times. It is compared with present-day concerts in order to voice an unfavourable opinion of the modern-day lack of rapport between artists sharing a stage, and the concert is evaluated through the rapport between the performers involved, the audience reaction and the quality of the vocal performances. The material performed is listed without comment, with the implication that its superior standard is a given. The performance is treated as entertainment, with (for example) its descriptions of the banter between the performers, but the music performed clearly has a status approaching that of high art due in part to its continuing appeal and existing longevity. The performance, therefore, is rated ‘bad’ because the original text was altered, ostensibly to meet the requirements of a 21st century audience. It is compared with B-movies and Game of Thrones, both examples of popular entertainment, and the set is likened to Willesden Junction. The performance is rated in comparison with the original text and analysed in terms of its departure from it. Overall, this production is firmly categorised as entertainment in comparison with the original text which is high art. Cavendish clearly considers the show to be the cheapest kind of entertainment – a star vehicle with gratuitous sex scenes – to titillate an audience who would struggle with anything more demanding. The reviewer demonstrates a solidly reactionary response and an unwillingness to examine any potential interest raised by this particular interpretation.

The performance, therefore, is rated ‘bad’ because the original text was altered, ostensibly to meet the requirements of a 21st century audience. It is compared with B-movies and Game of Thrones, both examples of popular entertainment, and the set is likened to Willesden Junction. The performance is rated in comparison with the original text and analysed in terms of its departure from it. Overall, this production is firmly categorised as entertainment in comparison with the original text which is high art. Cavendish clearly considers the show to be the cheapest kind of entertainment – a star vehicle with gratuitous sex scenes – to titillate an audience who would struggle with anything more demanding. The reviewer demonstrates a solidly reactionary response and an unwillingness to examine any potential interest raised by this particular interpretation. The performance, with its clear message and unmistakably feminist agenda, is considered to be good, in spite of a negative comment relating to the first half of the show. It is compared to other productions less brutal; Whaley describes Katherine as being beaten onstage and suggests that this abuse is ‘generally left off’, but such physical abuse is surely an addition on the part of this particular director and does not feature in the text itself. The performance is evaluated through the way in which it addresses the abuse of women and their unequal status in society in its chosen 1916 context. Finally, this production is treated as high art, and moreover, as art that is important because it seeks to educate and to highlight a societal problem.

The performance, with its clear message and unmistakably feminist agenda, is considered to be good, in spite of a negative comment relating to the first half of the show. It is compared to other productions less brutal; Whaley describes Katherine as being beaten onstage and suggests that this abuse is ‘generally left off’, but such physical abuse is surely an addition on the part of this particular director and does not feature in the text itself. The performance is evaluated through the way in which it addresses the abuse of women and their unequal status in society in its chosen 1916 context. Finally, this production is treated as high art, and moreover, as art that is important because it seeks to educate and to highlight a societal problem.