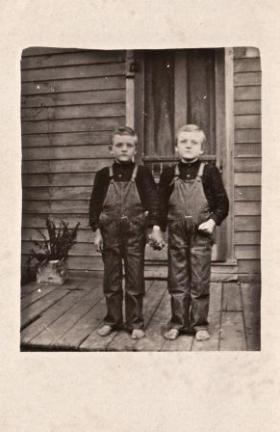

This post is about Muriel Spark’s short story The Twins, and the first thing I have to note is that if you search for ‘creepy twins’ in Google Images, you get a whole load of stuff that you really, really don’t want to see: ‘creepy’ in every sense of the word. But I did manage, by peeking through my fingers and scrolling down as quickly as I dared, to find several useful and really quite horrible images with which I shall pepper this post. You’ve been warned…

The Twins is not much of a story, really. An I-narrator recounts the events of a couple of visits to her friend Jennie’s house, once when the twins are five and again when they are twelve. If we are to believe what the narrator tells us – and I’ll explore this in more detail a little later on – the twins are born troublemakers whose angelic appearance belies their true nature. The story consists of six incidents in which it appears that a misunderstanding has occurred, but these ‘misunderstandings’ are in fact deliberately engineered to create disharmony amongst the characters. Eventually the narrator is moved to make an excuse to leave the house, without any intention of returning.

The six incidents are as follows: 1) the loan of a half-crown, in which little Marjie creates discord by not revealing all the necessary details; 2) the business with the tops, in which little Jeff lies outright; 3) Jennie reporting that Simon said the narrator looks ill and haggard, when the reader has overheard the conversation in question and knows he did nothing of the kind; 4) the biscuits and the mice – again, the reader knows that Jennie packed the biscuits and put them in the narrator’s room; 5) the business with the petrol money; 6) the most serious incident of them all: Mollie and Simon’s alleged misbehaviour in the kitchen.

The text world of The Twins is one in which everything can be questioned and even the most innocuous remark can cause great offence. This is a story about truth and about the telling of stories. And, what with it being a story, and being a story written by Muriel Spark, we mustn’t forget that actually none of it is true anyway. The reader believes what s/he is told by the first-person narrator, because that is what readers are inclined to do, but there are instances when the narrator herself is less than honest, if her words are to be taken at face value. For example,

“When I returned, these good children were eating their supper standing up in the kitchen, and without a word of protest, cleared off to bed before the guests arrived [p. 323*].”

Knowing what we do about the twins at this stage, in what sense are they ‘good’ children? There are two possible answers here: 1) they are good children and we can’t believe what the narrator has told us previously; 2) we are to understand that the word ‘good’ is heavily ironic in this sentence. Another example of the narrator’s possible duplicity occurs slightly previous to this episode on page 322:

“I munched [a biscuit] while I looked out of the window at the calm country sky, ruminating upon Jennie’s perennial merits.”

(Note the lovely inversion of the pathetic fallacy: the calm country sky in no way reflects the tension running through the country home.) It is strange to find the narrator pondering Jennie’s good points when she catches Jennie lying earlier that day:

“‘Thin and haggard indeed!’ said Jennie as she poured out the tea, and the twins discreetly passed the sandwiches [p. 322].”

Simon doesn’t say ‘thin and haggard’ at all. What he says is: “‘Why, you haven’t changed a bit… A bit thinner maybe. Nice to see you so flourishing.'” [p. 322] But Simon’s words are also part of what the narrator tells us, so whom can we believe?

For an explanation, we might look to the twins discreetly passing the sandwiches as the parent behaves in the way in which she has been taught to behave by her offspring, for this is a story in which the usual roles are topsy-turvy. “‘You’ll ruin those children,'” says Jennie to Simon, but in fact the reverse happens: the children ruin their parents in a startling role-reversal. The narrator tells us in the closing paragraphs that the twins gaze on their parents ‘with wonder, pride and bewilderment’, as they regard ‘the work of [their] own hands’ [p. 325]. But once again, this is what the narrator tells us, and the behaviour of all concerned is explained away in the narrator’s tenuous comparison of an expression on the twins’ faces with that of a portrait painter she once saw at the Royal Academy. But if these sentences were removed from the story, how could we explain the strange behaviour of Jennie and Simon? We rely on the narrator to tell us the truth, but there is no guarantee that what we are told is not a fabrication on the part of the narrator; the twins might well be the little angels everyone believes them to be and the narrator could be leading the reader by the nose just in order to have a good story to tell. Happy couples do not make narratives because there’s no narrativity in contentment. So there are two ways in which we can read a sentence such as the following:

“In these surroundings she seemed to have endured no change; and she had made no change in her ways in the seven years since my last visit [p. 322].”

We could take the sentence at face value: Jennie has made no change and all is as idyllic as before; or, the narrator is being disingenuous here and Jennie has changed – she has become the same kind of devious mischief-maker as her children. In the context of the rest of the story, the second option seems the most likely, but if we admit this, then we are admitting that the narrator has just lied to us. In addition, the tentative note of ‘seemed’ appears in the first clause, but not, as it should, in the second. If we admit then, that the narrator lies to us occasionally, how much more of this narrative is not quite true?

For the sake of moving the discussion on, let’s assume that the narrator is indeed telling us the truth and that those moments of apparent disingenuousness are to be read and understood ironically. To be fair, the story is constructed so as to convince the reader of the narrator’s veracity. The first incident which occurs to make us suspect the twins of not being quite so lovely is the episode in which Marjie asks for a half-crown. This coin is to provide Jennie with change for the baker’s man, but Marjie does not reveal as much: she simply says that she wants it, which is not enough to induce the narrator to provide her with a coin, thus landing the narrator in some trouble with Jennie. Marjie is only five years old at the time, and we could believe that she has made a mess of this errand owing to youthful inarticulacy, had we not just been told how advanced the twins are for their years. (And in fact, Jennie herself says that she would never allow the children to ask for money when she has moments before instructed Marjie to do exactly that. No wonder the poor narrator is left floundering.)

Marjie’s odd behaviour is still in the reader’s mind when it comes to the fuss about the tops, which is why we accept the narrator’s version of Jeff’s behaviour so readily. The narrator provides us with two pieces of information which put together demonstrate that Jeff is telling an outright lie when he insists that he was playing with the blue top: Jennie points out that the top Simon has taken to pieces is the red one, and the red one belongs to Jeff; later, when the narrator goes outside, she sees ‘the small boy spinning his bright-red top on the hard concrete of the garage floor’ [p. 320]. From this, we can deduce that Simon did manage to piece together Jeff’s top after he’d taken it apart, and that Jeff played with this top before taking it apart again in order to cause trouble between his parents. If it weren’t for these two pieces of information, we could easily believe that Simon had broken Jeff’s top and hadn’t wanted to admit it.

Not that this incident does cause trouble between Jennie and Simon, of course – not on the surface, anyway. Everyone is too polite to make a fuss and this is precisely what allows the twins to get away with their little fibs and fabrications. Repeatedly we hear characters enjoin the narrator not to mention what has happened, or that words have been spoken, because Jennie doesn’t want to upset Simon, and vice versa. When the narrator visits Jennie and Simon for the second time, it is no longer the twins causing trouble: it is Jennie and Simon, both of whom have adopted this behaviour from their creepy kids. And they are creepy: eerily beautiful, spookily well-behaved and exceptionally intelligent: we hear from Jennie when the twins have reached the age of twelve how both Marjie and Jeff have won scholarships. In a world where everything is suspect and every remark subject to scrutiny, Jennie’s comments about Marjie’s geography are potentially explosive: “‘If it hadn’t been for the geography she’d have been near the top. Her English teacher told me.'” In any other story world, this remark would be taken as ordinary parental boasting and perhaps also as a way to introduce the English teacher, Mollie Thomas, but in this world, the reader can easily imagine Jennie’s comments becoming part of yet another fraught and private conversation in which one of the speakers uses the words ‘Please don’t say anything’. Each lie or half-truth opens up for the reader a little text world which may or may not exist: Simon and Mollie’s alleged dalliance in the kitchen, for example – what happened here? The narrator says ‘She’s in the kitchen,’ [p. 324] when Jennie asks where Mollie is, and before you know it, Simon is writing to the narrator berating her for insinuating that he and Mollie were ‘behaving improperly’ [p. 325]. The narrator by this time has quite sensibly cut her losses and left Jennie and Simon’s troubled house, never to return.

Can’t blame her. Stay away from the creepy twins!

*Spark, M., 2002. The Complete Short Stories. London: Penguin.