Literature, s. learning, skill in letters.

Dr Johnson’s 1755 Dictionary

This definition of ‘literature’ provided by Dr Johnson was penned in the middle of the eighteenth century. Here he is as played by Robbie Coltrane in the third Blackadder series:

This is such a clever episode, and it’s one of my favourites. The line which makes me laugh every time is Prince George’s response to Dr Johnson’s explanation of the purpose of his famous dictionary:

DR JOHNSON: It is a book, sir, that tells you what English words mean!

PRINCE GEORGE: I know what English words mean! You must be a bit of a thickie.

Dr Johnson was not, of course, thick, and his definition of ‘literature’ was perfectly adequate for the middle of the eighteenth century, when the novel was in its infancy. As Jonathan Culler notes in his Literary Theory: A Very Short Introduction, ‘[p]rior to 1800, literature and analogous terms in other European languages meant “writings” or “book knowledge”‘ (1997:21). But the literary world has grown exponentially since then in terms of production, reception, criticism and theory, and Johnson’s definition now looks to be sadly lacking. So, if we were going to define ‘literature’ for the twenty-first century, where would we start?

What is literature?

Some of my initial thoughts were as follows.

- Literature can be anything written down, or any kind of text consisting of words and/or images.

- Literature is a crafted piece of work, such as a novel, play or poem etc., consisting of words and/or images in which the form and the content of the work are arguably inseparable, or alternatively, a text in which the aesthetic function is privileged over the communicative.

- Literature is both a response to and a product of its socio-historical and cultural context.

These ideas are perhaps drawing a little closer to a more contemporary definition of ‘literature’, but to my mind, they still do not provide a clear picture of what ‘literature’ really is. I had a look at how literature is defined in a couple of modern dictionaries, and this is what I found:

Chambers Dictionary

literature n.

1 The art of composition in prose and verse

2 The whole body of literary composition universally, or in any language, or on a given subject, etc.

3 Literary matter

4 Printed matter

5 Humane learning

6 Literary culture or knowledge

…and here’s the second definition:

Shorter Oxford English Dictionary

literature, n.

[(French littérature from) Latin lit(t)ratura, from lit(t)era LETTER noun: see -URE.]

1 Acquaintance with books; polite or humane learning; literary culture. Now arch. rare. LME

2 Literary work or production; the realm of letters. L18

3a Literary productions as a whole; the body of writings produced in a particular country or period. Now also spec., that kind of written composition valued on account of its qualities of form or emotional effect. E19

-b The body of books and writings that treat of a particular subject. M19

-c Printed matter of any kind. colloq. L19.

The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (hereafter SOED) is of course a much larger work than the Chambers Dictionary (hereafter CD), and its entries include etymological details and examples of usage, which the CD doesn’t. Hence we have in the SOED a history of the word ‘literature’, including the sense used by Dr Johnson (number 1) marked here as ‘arch. rare. LME’. By the late eighteenth century (number 2), the sense of ‘literature’ has expanded to acknowledge the works themselves, rather than serving as some kind of pseudo-adjective to describe a particular attribute of those who read books and letters. Sense 2 is less centred on the human reader of texts and more focused on literary output, although this output is still very much connected with ‘the realm of letters’. (This makes sense, of course, when put into historical context.) Sense 3 seems to be a more current definition of ‘literature’ accepted by the SOED, and this sense is divided into three parts which reflect the expansion of the term’s usage over the nineteenth century. It’s worth noting, however, that sense 3c, ‘Printed matter of any kind’ is still labelled colloq., as if it is in some way inferior to the other senses.

The CD entry for ‘literature’ is set out differently. There is no etymological or historical information, and no concrete examples are provided. The entry is split into six senses, which seem to be listed in order of decreasing relevance, with 1 being the most commonly used sense and 6 being the least. We can see then, that CD senses 5 and 6 more or less reflect the SOED’s sense 1 in that they are historical meanings no longer or rarely used. ‘Printed matter’ appears at CD sense 4, because it is used more often than 5 or 6, but less often than 1, 2 or 3 (and note there is no ‘colloq.’ value judgement here!). CD sense 3 is too vague for me – I honestly don’t really know what might be meant by ‘literary matter’. Sense 2 describes the existing body of work and the top sense – CD sense 1 – refers to its production.

I’d like to note two things of interest in the comparison of these two definitions. First, the SOED attempts to define why a work might be considered ‘literature’ in sense 3a: literature is ‘that kind of written composition valued on account of its qualities of form or emotional effect’. This, of course, raises heaps of questions: what sort of qualities are valued? Who decides what qualities are valuable? How does a reader recognise these qualities? What sort of emotional effect are we talking about here? – and so on – but it is not a dictionary’s job to answer these questions. The CD, however, perhaps wisely makes no attempt at all to comment on form or effect and sticks to a definition that is unquestionably true, but limited in scope: ‘literature’ is ‘[t]he art of composition in prose and verse’. The other point I wish to mention is the use of the word ‘humane’, which appears in both entries. Dictionary definitions inevitably lead to the search for other definitions, and CD lists the following as one of the senses of ‘humane’: ‘humanising as humane letters, classical, elegant, polite’. I think, then, that this sense is a reflection of the eighteenth century zeitgeist and its obsessive love affair with classical form, rather than any attempt to suggest that reading makes us all better human beings.

Well, dictionary definitions are all well and good, but they are designed for a very specific purpose and are perhaps not the best way to explore this question. Moreover, dictionaries do not define usage, they merely reflect it. A dictionary definition is not timeless or fixed, nor does it represent some kind of untouchable truth. So let’s set about this a different way, and try to provide answers to some fairly open questions.

1. If we want to think about literature as writing, then does the term apply to all written texts, or only to a specific kind?

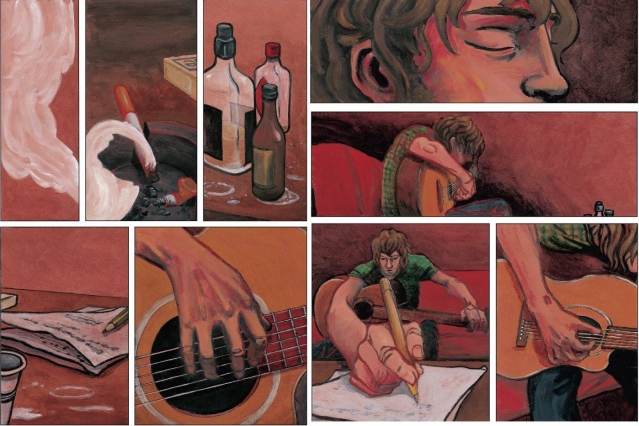

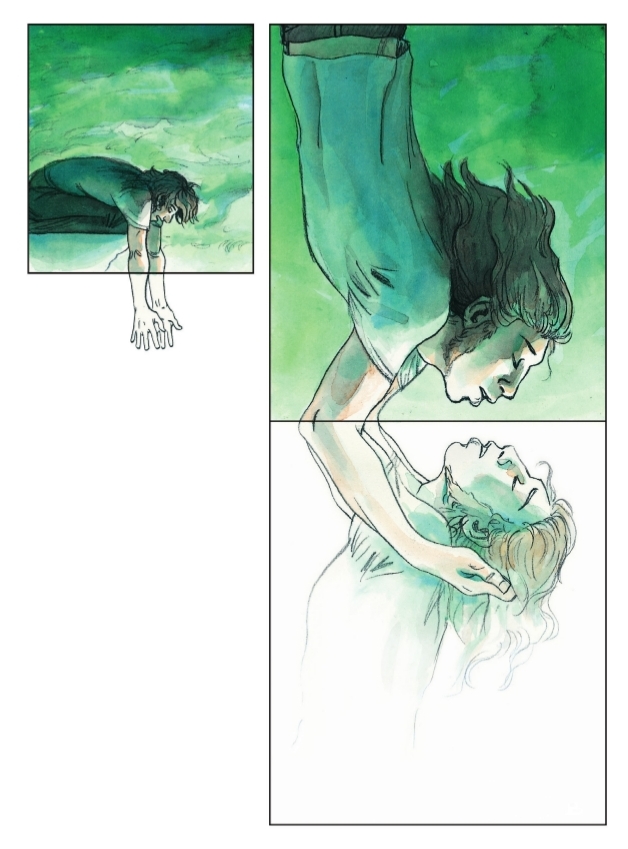

I’m always very keen to include comics (graphic novels if you must) under the heading of ‘literature’, which I’m aware others are not. For me, they are dense and rewarding texts: the words and images are read in conjunction and work together to create meaning, even when one is apparently undermining the other. But no doubt different people would include all sorts of different works when asked what they would classify as ‘literature’: for example, there have been many voices in favour of the inclusion of Terry Pratchett’s Discworld oeuvre. The fantasy genre, whose readers do tend to put the ‘fan’ in fanatical, throws up an interesting question. If we classify The Lord of the Rings as literature – and we do – why not Game of Thrones (for example)? Is it because the author of the former was a much-lauded Anglo-Saxon scholar and a professor of English? Or does Tolkien’s novel genuinely present properties that are lacking in Martin’s work? (And if so, what are these properties?)

Some texts will not be acceptable as ‘literature’ because the quality of writing is considered too low in standard. But who sets these standards, and what are they? To return to the example of Pratchett’s extremely popular Discworld series, many of these books are formulaic, over-long, and consequently dull – but Monstrous Regiment, Night Watch and Going Postal are really very good. On the other hand again, someone once tried to tell me that Pratchett is on a par with P G Wodehouse, to which my response was a thumping NO HE IS NOT. Pratchett’s comic timing is good, but Wodehouse’s is impeccable: he writes highly sophisticated sentences which turn exquisitely on numerous subordinate clauses to deliver the funny at exactly the right moment. Perhaps in the end it all comes down to a sense of grammar and an excellent ear. I don’t know. But I do know that Wodehouse is better than Pratchett.

I think, in fact, the question is asking for a distinction to be made between texts that are clearly communicative and functional, and texts that are ‘art’. But even here, the line has to be drawn somewhere, and while it is easy to make a distinction between a novel and a shopping list, what do you do if that shopping list has a kind of poetic coherence, or if it makes a poignant comment on the human condition that makes reading it an emotional experience? What then?

2. When does ‘literature’ become ‘Literature’?

I’ve taken the capital L to mean that a work is sanctioned or ratified and can henceforth be considered ‘good’ and ‘worthy of study’.

So, works of literature become ‘Literature’ when:

- an over-privileged and overbearing white male such as Harold Bloom decides that a work should be included in the literary canon;

- a work is added to the curriculum and taught in schools, colleges and universities;

- a work is nominated for a literary prize;

- a work chimes with the zeitgeist; when its theme, form or execution fits the prevailing cultural preferences.

All of which means that ‘Literature’ can go back to being ‘literature’ as soon as it falls out of favour. It’s not necessarily a one-way street we’re talking about here. Writers who were once lauded can sink into obscurity, but there is the possibility of rescue when a change in the cultural wind makes them fashionable once again.

I don’t think much of ‘Literature’, really. It’s an interesting phenomenon in its own right, especially in the contribution it can make to the study of culture, but I certainly can’t reconcile myself to the idea of a literary canon.

3. If literature possesses a quality that we recognise as ‘literariness’, then how is this recognised?

To answer this question, one would have to consider the notions of ‘foregrounding’ and ‘deviance’ put forward by the Prague School scholars at the beginning of the twentieth century. It’s about language, and when language draws attention to itself in some way, through use of rhyme, metaphor, and all the many many other literary devices. If we are using metalanguage – language about language – to describe what’s going on in the text, then that text has called attention to its FORM and therefore possesses literary qualities (even if it is not considered literature).

4. Is literature best thought of, beginning perhaps from linguistics, as a form of ‘peculiar language’?

This is Prague School territory again, and I think the New Critics could also be brought into this discussion, but essentially, the answer is no. Some literary works include remarkably non-literary language – Hemingway, for example, and see Terry Eagleton’s comments on ‘This is awfully squiggly handwriting!’ in Knut Hamsun’s novel Hunger (from Eagleton’s Literary Theory, p. 6). The context is literary, but arguably not the style – although I think this statement is problematic. For example, Hemingway’s sentences are simple, but this doesn’t mean they’re not carefully crafted to achieve a certain effect.

Perhaps literature, or literary language, is best thought of as being differentiated from other language use in terms of its function rather than its form. What’s it there for? What is it doing? Why should we read it? …which brings me to the next question.

5. What is literature for?

I came up with seven possible responses to this one.

- for entertainment, to tell a story;

- for edification and instruction;

- for the dissemination of an ideology, whether done knowingly or not;

- to provoke discussion, to enlighten, to share, to inform, to make readers think, to shock, to awaken in a mental sense;

- to form part of a nation’s cultural life; to create and perpetuate a way of thinking and a body of myths and legends;

- to bring people together;

- to deceive – remember Plato banned the poets!

And the final question:

6. Does literature make anything happen?

Taking point 3 above, yes. Literature can be enormously powerful, for good or for bad. Stories can become myths, and the myths can become ways of thinking and being. Literature can reveal and shatter normalised thinking patterns, but it can also create them.

In addition, if someone powerful disagrees with what you write, you lay yourself open to hostile criticism or even place yourself in physical danger – look at Salman Rushdie’s experience of the fatwa, and consider Timothy Bell’s recommendation that Hilary Mantel be investigated by the police following the publication of her short story The Assassination of Margaret Thatcher: 6 August 1983. Literature can create culture and cultural revolutions. One has only to look at the historical – and contemporary – persecution of writers to realise that state governments take very seriously the written output of citizens. English PEN certainly has its work cut out.

I’m not sure I’ve got any closer to answering the question ‘What is literature?’, but there’s some food for further thought here at least.

I’m kicking off this year’s

I’m kicking off this year’s

d, the microphone) that Tazane is onstage singing, but we can guess from the spiky balloons and large spaced-out font of the letters that he is not crooning softly, but belting out the words. The colour scheme reinforces this impression: think how these panels would differ if rendered in pale blue or green, for example.

d, the microphone) that Tazane is onstage singing, but we can guess from the spiky balloons and large spaced-out font of the letters that he is not crooning softly, but belting out the words. The colour scheme reinforces this impression: think how these panels would differ if rendered in pale blue or green, for example.