I started reading Asterix during my middle school years, and I well remember the scuffling and elbowing which regularly took place in the school library as everyone fought to grab at the titles on the Asterix shelf. My Aunty Clo and Uncle Jim bought me Asterix the Gaul, my first Asterix book, for Christmas in 1980 when I was nine years old, and I have read and re-read these books ever since. I saved my pocket money to buy them from WHSmith when I had to give up on the library because everyone else’s elbows always seemed to be far sharper and harder than mine and I could never get to the Asterix books without suffering various blows to my weedy little person. In those days – and this may still be the case – Asterix books came in two sizes, and you could buy a copy of the book in a size slightly smaller than A5 which cost 75p. These days, I have in my possession every Asterix book in both English and French. The books are scruffy, foxed and yellowed, but all that’s just proof of how long I’ve had them, how often I’ve read them and how much I love them.

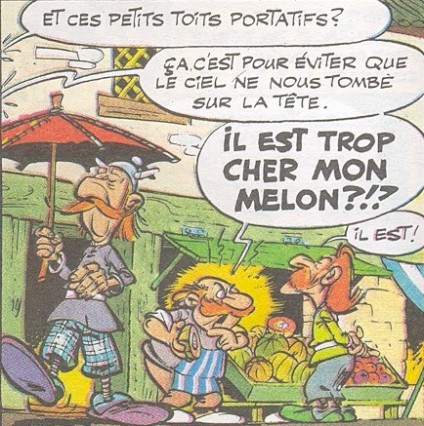

I say ‘every Asterix book’, but that’s not entirely true. Goscinny was the partner who wrote the scripts and the quality of the storywriting rapidly faded after his untimely death: Asterix in Belgium was the last book Goscinny and Uderzo produced together. Uderzo still struggles gamely on alone, but the Asterix books have come to be aimed at a much younger market and all the joy of the original has vanished. The drawings are as beautiful as ever, but the sophisticated wordplay is long gone. There’s a new book due out very soon, if it’s not out already, and I’m not going to read it. I just can’t bear to see what has become of Asterix. I stuck with it for as long as I could, and I’ve enjoyed some recent compilations: Asterix and the Class Act, for example, which appeared in 2003, brought together some previously unpublished short stories, and 2007 saw the publication of Astérix et ses Amis, in which a number of artists paid tribute to this character with their own very amusing versions of the plucky little Gaul and his companion envelopé. But to be honest, everything from Asterix and Obelix All At Sea onwards just hasn’t been up to scratch.

I’ll return now, though, to the good stuff, because I have, after all, placed Asterix in joint second place as one of My Top Five Favourite Comic Books. I’ve chosen one Asterix book dating from the years of the Goscinny/Uderzo partnership to represent the entire oeuvre, rather than trying to write about the whole lot in one blog post. The book I’ve chosen is Asterix and the Roman Agent, or La Zizanie in French; semer la zizanie is to sow discord, or to stir up ill-feeling, and a ‘zizanie’ is ‘a type of invasive weed’. The name of the Roman Agent – Convolvulus – is the Latin term for bindweed, and anyone who has bindweed in their garden knows how quickly it spreads and how destructive it is: it takes over and chokes everything else. It’s extremely difficult to get rid of bindweed once you’ve got it, because it’s also incredibly pervasive. On the subject of the Agent himself, Peter Kessler notes in The Complete Guide to Asterix that ‘[t]his is the only adventure that includes a ‘symbolic’ character. Convolvulus, the Roman Agent, is the physical embodiment of social disruption. Injecting him into the Gaulish Village has the effect of a moral tale about the danger of gossip and deceit’ (p. 41).

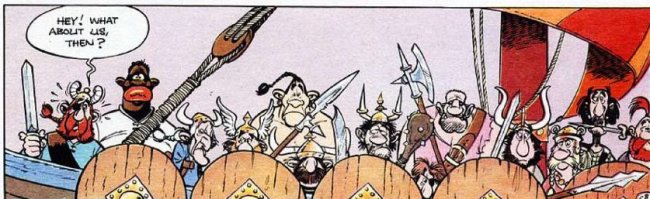

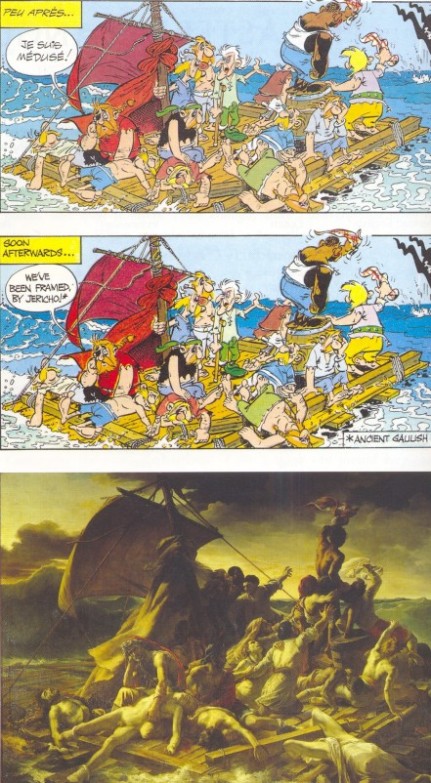

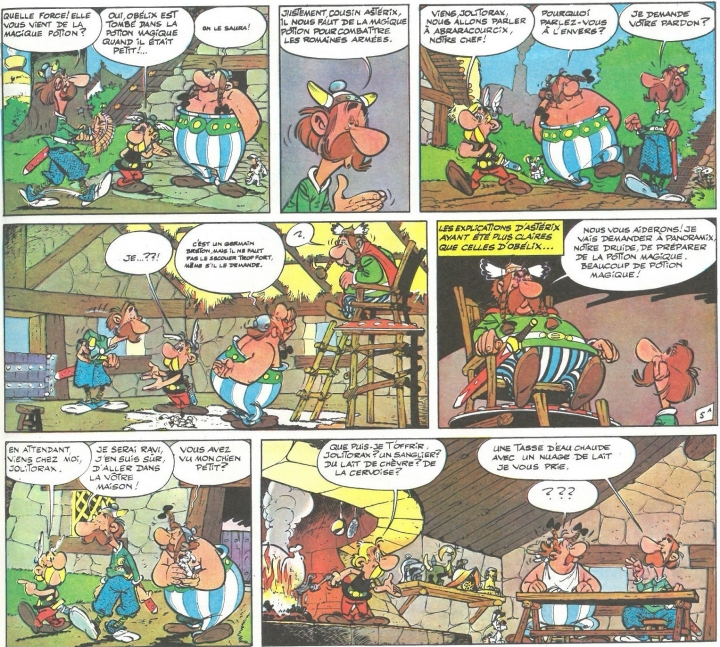

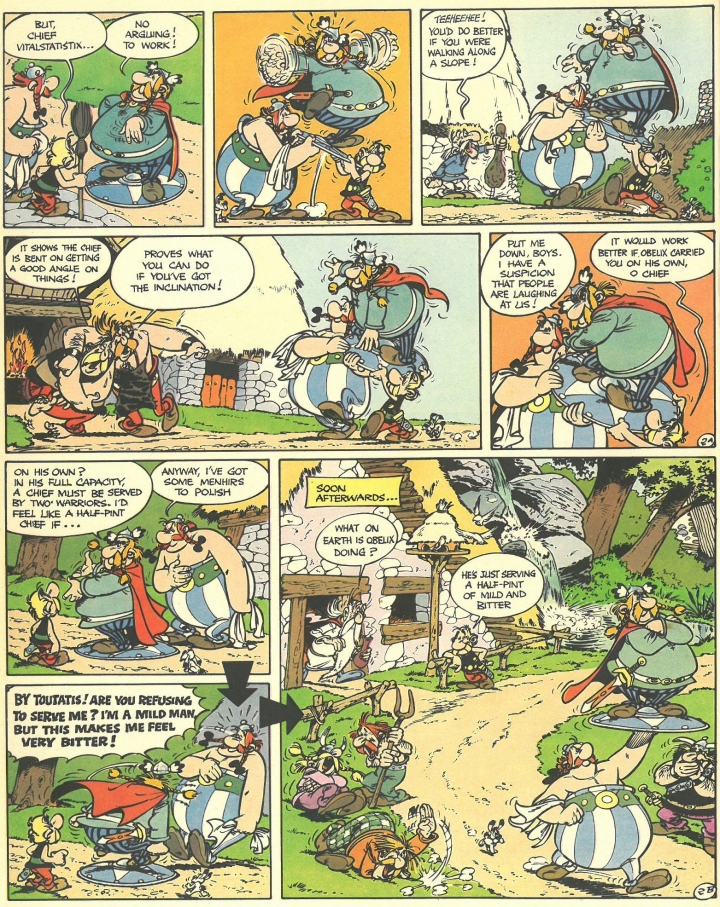

I’ve chosen The Roman Agent for several reasons: the story is excellent, tightly constructed and beautifully executed. The repetition of a scene involving the village women standing in a queue for fish provides a neat frame for the arrival and departure of the titular zizanie, and of course, it’s very funny: the reader knows there’s going to be a fight as soon as Unhygienix’s fish appear in any Asterix book, and frankly, I’d be hard pushed to name anything funnier than Uderzo’s fabulous drawings of the Gauls slapping each other with fish. In fact, The Roman Agent contains some of Uderzo’s most amusing images: the mother hen and her row of six little chicks calmly watching yet another fight on page 20 for example, and the bemused expressions on the faces of the pirates on page 10 when the Romans are too busy bickering with each other to pay the pirates any attention. The book also has some of the funniest lines: when spying on the Roman camp, Fulliautomatix warns Unhygienix ‘Try not to smell!’ (p. 27); the captain of the ship escorting Convolvulus to Gaul says of the look-out in the crow’s-nest that ‘No one’s to listen to him! He’s been sent to Coventrium!’ (p. 9) and on page 30, Obelix complains ‘No one ever explains anything to me! They just keep me around because I’m ornamental!’ Obelix isn’t the only one in the dark and the writers milk the ensuing confusion for every last drop of humour: the Romans are too thick to keep up with Convolvulus’s plans and no one knows whether they’ve got the magic potion or not.

So we have some tight plotting, lots of laughs, and a couple of interesting touches to boot: Uderzo is always very inventive with speech bubbles and in this book we see the colour of the bubbles change from white to pale green to dark green as the zizanie does his work and everyone gets angry. We also see this happen in reverse: on page 18, Obelix storms out of Asterix’s hut after an argument, but he calms down as he marches away and the colour of his speech bubbles fades back to white before Obelix rushes back to make up with Asterix. On page 36, flowers appear in the Roman Centurion’s speech bubble to indicate a false honeyed tone when he asks ‘Did you by any chance fail to understand me?’ ‘Well, to be honest…’ replies the legionary. ‘Get on with it!’ shouts the Centurion (bold lettering always denotes shouting, of course). And no critique of The Roman Agent would be complete without a mention of the lovely self-referential moment on page 14 when Impedimenta bellows ‘Well, let me tell you that if anyone should ever be fool enough to write the story of our village, they won’t be calling it the adventures of Vitalstatistix the Gaul!!!’ This is just wonderful, because now the reader too is involved in the spreading calumny: on the page following, when Geriatrix’s wife claims that Mrs Asterix, if she existed, should be the first lady of the village, we know this to be true, because the books we read are entitled ‘The Adventures of Asterix the Gaul’ (not Vitalstatistix), so we are forced in this way to take sides. And as a result, we would be in line for a smack around the chops with one of those fish.

As well as the moments that make The Roman Agent special, all the usual things we’ve come to expect from an Asterix book are here too: lots of fights, obviously, including fish fights and cat fights; the pirates, who this time scuttle their own ship; the banquet at the end following one final punch-up; Julius Caesar getting grief from the Senate…it’s all here. And what’s nice about this book is that the Romans provide us with at least as much entertainment as the Gauls. There are gags galore involving psychological warfare (hitting someone with a club), and the Romans’ ability to bicker amongst themselves is seemingly endless. The Romans come out of this book very well, because Convolvulus is the main baddie – but there’s even scope for a little sympathy for Convolvulus. It’s a nicely balanced book and a worthy representative of the Asterix canon.

For more about Asterix on Aunty Muriel’s Blog, see Asterix in Translation: The Genius of Anthea Bell and Derek Hockridge.

Bibliography:

Kessler, P., 1995. The Complete Guide to Asterix. London: Hodder.