What’s Yours is Mine

By Michael Symmons Roberts

‘Doors which yield to a touch of the hand…

permit anyone to enter.’

Thomas More, Utopia

It was our game, to drive at night into their city,

scan the streets, choose a house at random

and stroll in mid-evening as the householders

were finishing, say, a birthday dinner.

We watched them look up, terrified but mute.

We picked lambs off their plates, emptied their glasses

then ran upstairs, threw open drawers

tried on jackets, fingered through their journals,

pocketed the odd keepsake – scarf, set of car keys,

half-read book, a piece of underwear for shame.

We tried to get a rise from them by breakage:

a cabinet of crystal cups, statuettes of local gods,

but they are patient in their sad-masks.

Such acquiescence, you knew they saw you straight,

and even so would give you everything.

Our only rule: we never touched them.

Save one time I saw a blue heart-shaped soap

clutched in a woman’s hand and something in her

would not give it up to me for all the world.

I have it somewhere. Let me find it.

Published in the London Review of Books, 18 May 2017, p. 23

Figure and ground in Michael Symmons Roberts’ ‘What’s Yours is Mine’

The cognitive categories of figure and ground facilitate discussion of how the reader’s attention is directed and assist in the positive identification of foregrounded items. Figures attract the reader’s attention whereas the ground consists of items that are neglected and/or deselected. In the case of the poem under consideration in this essay, the speaker of the poem and his/her companions collectively comprise the figure for the first three verses of the poem in that they move and act against the householders, who constitute the background all the while they remain static and undeveloped.

‘What’s Yours is Mine’ by Michael Symmons Roberts was published in the London Review of Books on 18 May 2017, appearing alongside another poem by the same writer entitled ‘Soliloquy of the Inner Emigré’ and an article on ‘Brexitism’ by Alan Finlayson. Given this context, it is fair to assume that the subject of Roberts’ poem is that of immigration, a highly contentious and emotionally-charged topic in the current political climate. In this reading, the householders represent an immigrant or ethnic community terrorised by those who cannot accept their presence. Nevertheless, this is not the only possible reading. When removed from the circumstances of its publication, the poem could equally be read as a metaphor for an oppressive political regime or an abusive personal relationship. Alternative readings such as these resonate behind any chosen interpretation and I see no reason to pin down one reading as definitive.

The poem describes a scenario in which the speaker and his/her companions enter the homes of the city-dwellers and cause havoc. The intruders’ motivation is not that of pecuniary gain (although some small items are looted as ‘keepsake[s]’), but merely to ‘get a rise from’ the ‘householders’, or in other words, to provoke some reaction from them. Their efforts are unsuccessful until the last verse, and the narrative change in the final lines is marked textually by a fluctuation in the figure/ground relationship coupled with a foregrounded presence of negation and a deictic pronoun shift.

The ‘dominant’ of the poem, or its larger organising principle, is the us/them dichotomy established in the poem’s title (yours/mine) and the first line: ‘It was our game, to drive at night into their city’ (my emphasis). This polarity is sustained throughout in the pronouns ‘we’ and ‘they/them/their’ until the final verse, when one of ‘them’ emerges from the background to become a figure through her unwillingness to relinquish the ‘blue heart-shaped soap’. Her defiance is marked against a background of acquiescence which had formerly characterised ‘them’, and this figure, previously one of the ‘sad-masks’, is now recognised as a woman. Equally, the speaker is no longer part of a larger ‘we’, but in the final verse becomes ‘I’ and ‘me’. The woman’s stand against the intruders has led to a recognition of the presence of the individual within a larger group in both parties: the woman as part of ‘them’ and the speaker as part of ‘we’. The poem’s ending is unrelentingly bleak, nonetheless. The last line comprises two complete sentences and the caesura created by the first full stop allows the reader a moment for the full impact of the preceding statement to sink in: ‘I have it somewhere. Let me find it.’ What happened to the woman is unknown, but the intruder is now in possession of the soap and broke the game’s only rule (‘we never touched them’) to get it.

The next section of this essay takes a closer look at figure and ground in the poem to further elaborate on the points already made. The poem comprises four verses each of five unrhymed lines, and a mixture of long and short sentences. I have already mentioned the devastating effect of the caesura in the final line, and in fact, this structure is mirrored in the first line of the final verse: ‘Our only rule: we never touched them.’ This rule has clearly been broken in the poem’s final line and the enormity of this event is foregrounded in the parallel construction of these lines, both of which are uncharacteristic of the rest of the poem, where the lines run into one another in imitation of one half of a spoken dialogue. The speaker is relating to the listener (who may or may not be identified with the reader) details of a ‘game’. Given that the past tense is consistently used, one may assume that the game is no longer played, presumably because its object has been achieved. The first verse describes how the victims of the game were chosen: entirely ‘at random’. The second verse shows the game in progress, with lists of actions performed and objects stolen; each of the latter takes temporary prominence before being deselected as the next item – with all its attendant implications – moves into focus. The intruders are a collective ‘figure’ here because almost every action in the first two verses belongs to them. Even the one exception performed by the householders (line 5) is an action embedded in another: the intruders, in subject position, watch the householders ‘look up’ and the following description (‘terrified but mute’) is rendered through the intruders’ eyes. As the intruders ransack the house, the full meaning of the poem’s title is made clear. The intruders violate the householders’ food, drink, clothes including underwear, means of transport, literature, even their private thoughts (‘fingered through their journals’). The third verse furnishes the reader with the object of the game, expressed in colloquial form: ‘We tried to get a rise from them’. The ‘but’ which follows in line 13 renders this construction implicitly negative: a ‘rise’ has not been obtained. The revelation of the game’s object occurs at the exact mid-point of the poem and this is the crux: what the intruders want is a reaction. When a reaction is obtained, albeit it one of static defiance (‘something in her / would not give it up to me for all the world’), the only rule is broken and the game is over.

The figure/ground relation is rather more complex in the third verse. The intruders remain the key attractor even in the active verbs attached to the householders in lines 14 and 15, because the viewpoint belongs to the intruders. Nevertheless, this position is clouded by foregrounded language attached to the householders. Alliteration draws attention to the ‘cabinet of crystal cups’, for example, and the precise meaning of ‘statuettes of local gods’ is unclear. (These statuettes may be family photographs, or shelf ornaments, but the phrase could also be taken entirely literally: this is one point in particular where the reader’s interpretation of the poem as a whole will dictate what form the statuettes take.) The pattern of past-tense verbs is broken in line 13 (‘they are patient’) and the householders are dehumanised and rendered faceless in the phrase ‘sad-masks’. The emergence of one of the householders as a figure in the final verse is anticipated in the preceding verse as the foregrounded items mentioned gradually draw the reader’s attention towards those persecuted rather than the persecutors. Finally, it is the woman’s reluctance to part with the ‘blue heart-shaped soap’ that changes the game.

I have not yet mentioned other texts brought into play by this poem, namely those referred to in the title and accompanying quotation. The title would seem to be a paraphrase of a marriage vow from the Book of Common Prayer (‘with all my worldly goods I thee endow’), and refers to a state in which goods become common property by mutual consent. The quotation from More’s Utopia similarly refers to a set-up in which theft is unimaginable. More’s utopian blueprint describes a society in which everyone’s possessions are identical, so there is no motive for robbery. By contrast, the intruders in Roberts’ poem steal only ‘keepsake[s]’ from the households they invade at random through doors which are left open. The motivation for their actions is not the acquisition of goods, but the exercise of power. Their intention is not robbery or assault, but humiliation and provocation. The intruders wish to assert their dominance over the householders and to strip them of all human dignity by treating them with heartless contempt.

This analysis has employed the cognitive categories of figure and ground to articulate that which is readily understood, but perhaps not otherwise so clearly demonstrated. The analysis has benefitted from the application of this framework in that the woman’s emergence as a figure and the speaker’s recognition of her as such has been effectively traced. The poem’s bleak ending is rendered all the more powerful once it is realised that the speaker has recognised an individual human being amongst the faceless ‘them’ that s/he is engaged in persecuting, but has carried out an act of violence towards the woman regardless of this insight. The speaker is not simply lacking in empathy, but is finally characterised as a being who is actively cruel and merciless.

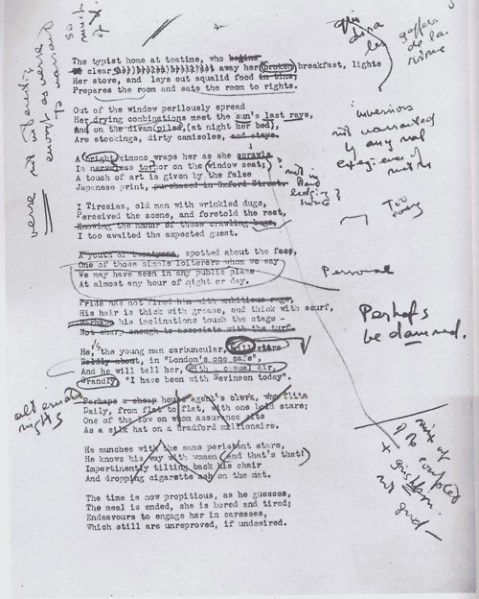

There are a multiplicity of voices in The Waste Land at any one time, which I have attempted to categorise below. The poem is informed by various religious and mythical texts: The Bible, the Buddha’s Fire Sermon, The Upanishads, Sybil and Tiresias from Greek and Roman texts, and, perhaps most important of all, the Grail Legend. Eliot makes numerous references to other literary texts; this category includes the self-referentiality of the poem itself in its various repetitions and parallelisms, and of course, Eliot’s own poetry (The Death of Saint Narcissus, the Sweeney poems, Dans le Restaurant). The poem features voices from the contemporary scene in its references to WWI, and, notably, songs from music-hall routines and American ragtime. There is birdsong from the nightingale, the hermit-thrush, a French cockerel, and the gulls of Part IV. There are voices from actual people now dead: Marie Larisch, ‘Mr Eugenides’ (whose proposition to Eliot in Part III was real), and Ellen Kellond, the Eliots’ housemaid, provided material for the scene in the public house. It has been suggested that Eliot himself and his first wife provide the voices in lines 111-138 (Southam, 1968: 160). There are the lines spoken by the characters of the poem, many of whom are imported from other literary texts and bring with them the voices from their original provenance. In addition to all this, there are numerous inarticulate speech-acts in which it is known that a speech act occurs, but the words themselves are unknown: chatter from the fish market, whispers, shouting and crying, ‘maternal lamentation’, voices from cisterns and wells, and this category can be stretched to include the ‘[s]ighs, short and infrequent’. The incessant noise of the cricket or the cicada is balanced against instances of the absence of sound: ‘the frosty silence in the gardens’ or the dry stone over which no water flows.

There are a multiplicity of voices in The Waste Land at any one time, which I have attempted to categorise below. The poem is informed by various religious and mythical texts: The Bible, the Buddha’s Fire Sermon, The Upanishads, Sybil and Tiresias from Greek and Roman texts, and, perhaps most important of all, the Grail Legend. Eliot makes numerous references to other literary texts; this category includes the self-referentiality of the poem itself in its various repetitions and parallelisms, and of course, Eliot’s own poetry (The Death of Saint Narcissus, the Sweeney poems, Dans le Restaurant). The poem features voices from the contemporary scene in its references to WWI, and, notably, songs from music-hall routines and American ragtime. There is birdsong from the nightingale, the hermit-thrush, a French cockerel, and the gulls of Part IV. There are voices from actual people now dead: Marie Larisch, ‘Mr Eugenides’ (whose proposition to Eliot in Part III was real), and Ellen Kellond, the Eliots’ housemaid, provided material for the scene in the public house. It has been suggested that Eliot himself and his first wife provide the voices in lines 111-138 (Southam, 1968: 160). There are the lines spoken by the characters of the poem, many of whom are imported from other literary texts and bring with them the voices from their original provenance. In addition to all this, there are numerous inarticulate speech-acts in which it is known that a speech act occurs, but the words themselves are unknown: chatter from the fish market, whispers, shouting and crying, ‘maternal lamentation’, voices from cisterns and wells, and this category can be stretched to include the ‘[s]ighs, short and infrequent’. The incessant noise of the cricket or the cicada is balanced against instances of the absence of sound: ‘the frosty silence in the gardens’ or the dry stone over which no water flows. Given this cacophony of voices, to identify a single protagonist as Edmund Wilson tries to do is to attempt to impose a level of coherence on the poem that it arguably does not have. Wilson’s efforts to single out a voice and construct a narrative sequence ending in the death of the ‘hero’ are, finally, unconvincing (Wilson, 1922). He wants a story with a beginning and an end – rather like a quest, such as the search for the Grail – but the fragmentary nature of the poem coupled with its frequent instances of repetition renders the whole more like a frozen moment in which all time is suspended. The presence of prophetic figures such as the Sybil and Tiresias, plus the fake fortune-teller Madame Sosostris, lends some weight to this reading.

Given this cacophony of voices, to identify a single protagonist as Edmund Wilson tries to do is to attempt to impose a level of coherence on the poem that it arguably does not have. Wilson’s efforts to single out a voice and construct a narrative sequence ending in the death of the ‘hero’ are, finally, unconvincing (Wilson, 1922). He wants a story with a beginning and an end – rather like a quest, such as the search for the Grail – but the fragmentary nature of the poem coupled with its frequent instances of repetition renders the whole more like a frozen moment in which all time is suspended. The presence of prophetic figures such as the Sybil and Tiresias, plus the fake fortune-teller Madame Sosostris, lends some weight to this reading. The literary references of The Waste Land operate a two-way effect in which the works alluded to infiltrate and resonate throughout Eliot’s lines; simultaneously, Eliot’s reformulation of literary fragments invites a re-evaluation of the original texts. This is entirely consistent with the logic of Eliot’s argument in his essay ’Tradition and the Individual Talent’, in that a new work of art stems from that which has gone before and, in being assimilated into the existing body of literature, affects how pre-existing works are perceived. This process can be exemplified through discussion of Eliot’s borrowing of Enobarbus’ words to describe Cleopatra: Eliot changes only three words of the first line and a half of Enobarbus’ speech, thus the reference is unmistakable. The domineering character of Cleopatra is transported into Eliot’s lines which, in their turn, emphasise the element of voyeurism inherent in the scene and question the nature of the relationship between art and artifice.

The literary references of The Waste Land operate a two-way effect in which the works alluded to infiltrate and resonate throughout Eliot’s lines; simultaneously, Eliot’s reformulation of literary fragments invites a re-evaluation of the original texts. This is entirely consistent with the logic of Eliot’s argument in his essay ’Tradition and the Individual Talent’, in that a new work of art stems from that which has gone before and, in being assimilated into the existing body of literature, affects how pre-existing works are perceived. This process can be exemplified through discussion of Eliot’s borrowing of Enobarbus’ words to describe Cleopatra: Eliot changes only three words of the first line and a half of Enobarbus’ speech, thus the reference is unmistakable. The domineering character of Cleopatra is transported into Eliot’s lines which, in their turn, emphasise the element of voyeurism inherent in the scene and question the nature of the relationship between art and artifice. The living boys are substituted for statues and Eliot’s description of them is therefore ekphrastic, as indeed, is this whole section of the poem from lines 77-106. Shakespeare’s Cleopatra is herself reckoned to be even more beautiful than an artistic depiction of Venus which flatters the goddess. The comparison of art and artifice continues in the description of the artificial fragrances which feature heavily in the scene: Eliot’s perfumes are cloying and ‘synthetic’, producing a disorienting, narcotic effect which renders the senses ‘troubled, confused’, particularly when coupled with the refracted light from the many doubled reflections of candle-flames and jewels; similarly, the perfumes emanating from Cleopatra’s barge have an intoxicating effect not only on the humans present, but also on the wind itself. Enobarbus’ eloquent admiration of Cleopatra is unusually expressive for such a moderate character as he; Eliot’s re-working of the speech invites the possibility that Enobarbus is purposely drawing attention to the deliberately staged quality of Cleopatra’s famous entrance.

The living boys are substituted for statues and Eliot’s description of them is therefore ekphrastic, as indeed, is this whole section of the poem from lines 77-106. Shakespeare’s Cleopatra is herself reckoned to be even more beautiful than an artistic depiction of Venus which flatters the goddess. The comparison of art and artifice continues in the description of the artificial fragrances which feature heavily in the scene: Eliot’s perfumes are cloying and ‘synthetic’, producing a disorienting, narcotic effect which renders the senses ‘troubled, confused’, particularly when coupled with the refracted light from the many doubled reflections of candle-flames and jewels; similarly, the perfumes emanating from Cleopatra’s barge have an intoxicating effect not only on the humans present, but also on the wind itself. Enobarbus’ eloquent admiration of Cleopatra is unusually expressive for such a moderate character as he; Eliot’s re-working of the speech invites the possibility that Enobarbus is purposely drawing attention to the deliberately staged quality of Cleopatra’s famous entrance. The Cleopatra equivalent herself, however, is not described in the parallel scene in The Waste Land. Instead, the focus switches to a painting displayed ‘[a]bove the antique mantel’ depicting Ovid’s story of the rape, mutilation and transformation of Philomela. The figure of Philomela features twice in Eliot’s poem at lines 99-103 and again in 203-206, the latter being a reference to Trico’s song in Lyly’s Campapse (Southam, 1968: 159). Philomela functions in the poem as an expression of the themes of sex and voyeurism. In Ovid’s story, Tereus mentally rapes Philomela before physically forcing himself upon her: ‘his mind’s eye shaped, / To suit his fancy, charms he’d not yet seen’ (Ovid, 1986: 136), both acts being witnessed also by the reader. Sex in The Waste Land is unsatisfactory, a duty or something to be endured (Lil and the typist), a profession (Mrs Porter and her daughter), or an act performed at the weekend with a stranger (Mr Eugenides). It is also barren and non-productive: Lil takes pills to induce a miscarriage in ‘A Game of Chess’, and in the Philomela story, the two sisters murder Itys, Procne’s son by Tereus, as an act of revenge. Eliot’s second reference to Philomela occurs immediately after the lines containing references to Eliot’s own Sweeney poems, a polite version of a bawdy WWI ballad (Southam, 1968: 168) and Paul Verlaine’s Parsifal. Sweeney appears here in his sexual character (’Sweeney Erect’), subject to the lust the Buddha preaches against in the Fire Sermon; Mrs Porter and her daughter are ‘notorious among Australian troops for passing on venereal disease’ (Southam, 1968: 168); Parsifal resists the temptation to sleep with the beautiful maidens put in his path and gains the Holy Spear with which he cures Amfortas, the Wounded King, who was seduced by Kundry and in consequence cursed with a wound that would not heal. Sex features in Eliot’s poem in terms of the violence of men, the seductive powers of women, and the danger of contracting disease through sexual contact; the rewards available to those who stay pure are encapsulated in the reference to Parsifal. In the wider context of the whole poem and the Grail legend which informs it, sex is at the heart of the misery experienced by the land and its inhabitants, all now laid to waste.

The Cleopatra equivalent herself, however, is not described in the parallel scene in The Waste Land. Instead, the focus switches to a painting displayed ‘[a]bove the antique mantel’ depicting Ovid’s story of the rape, mutilation and transformation of Philomela. The figure of Philomela features twice in Eliot’s poem at lines 99-103 and again in 203-206, the latter being a reference to Trico’s song in Lyly’s Campapse (Southam, 1968: 159). Philomela functions in the poem as an expression of the themes of sex and voyeurism. In Ovid’s story, Tereus mentally rapes Philomela before physically forcing himself upon her: ‘his mind’s eye shaped, / To suit his fancy, charms he’d not yet seen’ (Ovid, 1986: 136), both acts being witnessed also by the reader. Sex in The Waste Land is unsatisfactory, a duty or something to be endured (Lil and the typist), a profession (Mrs Porter and her daughter), or an act performed at the weekend with a stranger (Mr Eugenides). It is also barren and non-productive: Lil takes pills to induce a miscarriage in ‘A Game of Chess’, and in the Philomela story, the two sisters murder Itys, Procne’s son by Tereus, as an act of revenge. Eliot’s second reference to Philomela occurs immediately after the lines containing references to Eliot’s own Sweeney poems, a polite version of a bawdy WWI ballad (Southam, 1968: 168) and Paul Verlaine’s Parsifal. Sweeney appears here in his sexual character (’Sweeney Erect’), subject to the lust the Buddha preaches against in the Fire Sermon; Mrs Porter and her daughter are ‘notorious among Australian troops for passing on venereal disease’ (Southam, 1968: 168); Parsifal resists the temptation to sleep with the beautiful maidens put in his path and gains the Holy Spear with which he cures Amfortas, the Wounded King, who was seduced by Kundry and in consequence cursed with a wound that would not heal. Sex features in Eliot’s poem in terms of the violence of men, the seductive powers of women, and the danger of contracting disease through sexual contact; the rewards available to those who stay pure are encapsulated in the reference to Parsifal. In the wider context of the whole poem and the Grail legend which informs it, sex is at the heart of the misery experienced by the land and its inhabitants, all now laid to waste.