As promised in a previous blog entry, what follows is a discussion of the translation of some of my favourite Asterix gags. The translators’ modus operandi was to include as many jokes in the English translation as existed in the original French text, and on occasions, this task required a great deal of ingenuity on the part of the incomparable Bell and Hockridge.

I’ve included scans of the original illustrations – I’m not sure where I stand as far as image copyright is concerned, but I’m happy to remove the pics if requested to do so.

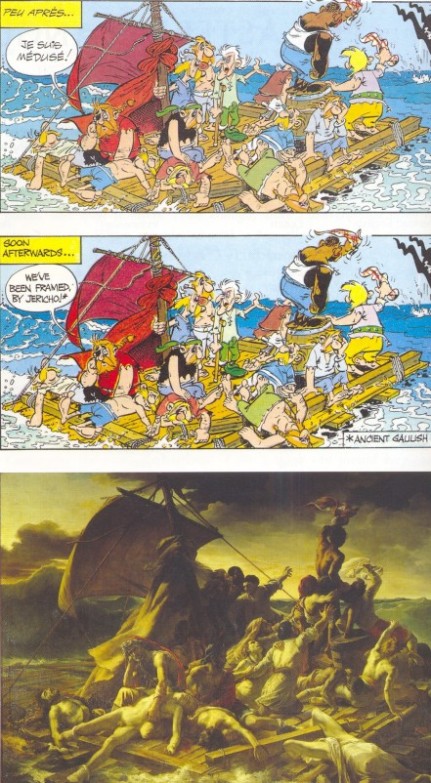

I. The Raft of the Medusa

First and foremost, the visual joke is in the artistic parody of Géricault’s famous painting, The Raft of the Medusa, shown above. The French text draws attention to this parody through the pirate chief’s use of the word médusé, in its phonological resemblance to the word ‘Medusa’. This resemblance is lost when the pirate chief’s words are rendered in English, however: médusé(e) translates approximately as ‘dumbfounded’. So, if the chief’s words are to carry out the same function in the English version of the joke, they must be changed, and the altered version reads: ‘We’ve been framed by Jericho!’

There are two references to Géricault’s painting here: (i) the chief speaks of having been ‘framed’, to mean ‘duped’ or ‘set up’, but the reference here is also to the physical frame of a painting, (ii) Jericho/Géricault: the ingenious translators have even managed to retain the joke based on phonological resemblance. The caption, ‘Ancient Gaulish artist’, alerts the reader unfamiliar with Géricault’s work to the parody of the painting.

The words had to be completely changed in order to retain the joke, but the translated version entirely captures the spirit of the original.

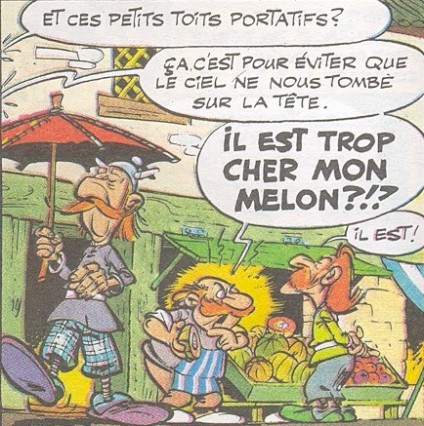

II. The melon gag from Asterix in Britain

The joke in the French version centres on the word melon. In French, ‘melon’ means both the fruit and a bowler hat. A half-melon is similar in shape to a bowler hat, as you can see in the picture. In this frame, the French are mocking the English way of dressing, or at least, the French idea of the English way of dressing: the chap to the left of the frame carries an umbrella, a fact which is discussed by Asterix and his English cousin; the grocer and his customer to the right of the frame are discussing the inflated price of a melon, thus adding the bowler hat to the umbrella, and – voilà! – we have an English businessman.

In English, the melon/bowler hat joke is lost. To keep a joke of some kind in the frame, the melon is no longer too expensive, this time it is rotten: ‘Oh, so this melon’s bad is it?’ This allows the customer to respond to the grocer’s outburst with the words ‘Rather, old fruit!’, thus creating a joke about rotten fruit and the refined speech of the English, as perceived by the French. The elegant and cultured ‘Rather, old fruit!’ is a rendering of the polished response in the French version – instead of ‘Oui,’ or even worse, ‘Ouai,’ the customer replies ‘Il est.’

Unfortunately, the tidy picture of the English businessman is lost. In addition, the coherency of the frame is also lost: in the French version, both sides of the frame work together to produce the joke (umbrella + bowler hat), but in the translated version, the man carrying the umbrella no longer has anything to do with the irate grocer and his customer. Nevertheless, ‘Rather, old fruit,’ still makes me laugh every time.

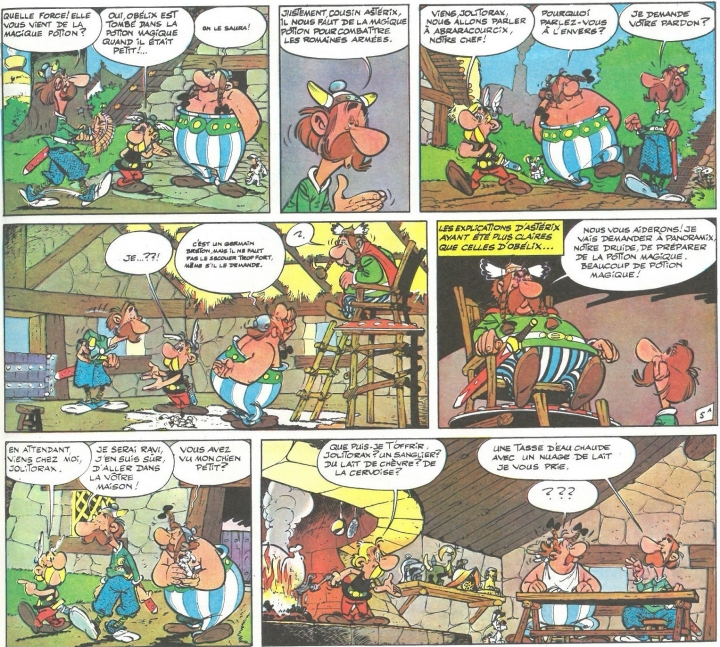

III. The godwottery joke: Asterix in Britain

The joke in the French version takes the form of a parody of English syntax. In English, the adjective is placed before the noun to which it refers, ‘the white house’, but in French the adjective usually comes after the noun, ‘la maison blanche’. The Jolitorax/Anticlimax character – Asterix’s English cousin – routinely places the adjective before the noun: la magique potion, les romaines armées, a practice which invites Obelix to ask ‘Pourquoi parlez-vous á l’envers?’ Obelix wants to know why this Englishman keeps putting words the wrong way round. In the third frame following this exchange, Obelix mischievously makes fun of Jolitorax by reversing his own word order: ‘Vous avez vu mon chien petit?’ (‘Have you seen my little dog?’) Two things to note here: firstly, petit(e) is one of a small number of adjectives that come before the noun in French (‘mon petit chien’ is the correct phrase). Secondly, Obelix uses the formal vous form, when Asterix characters habitually use the informal tu to address all and sundry, including Julius Caesar himself. Therefore, Obelix is mocking both the syntax of English through his reversal of word-order, and the formality of the English in his use of the vous form. (Click on the image to enlarge.)

Obviously, this joke is not going to work in English. We do not have an equivalent to the tu/vous distinction, and it would not make sense to the English reader if the usual noun/adjective order were to be reversed. To preserve the joke about the way in which English people speak, Anticlimax expresses himself in an excessively formal way, peppering his speech with interjections such as ‘I say,’ and ‘What’. Obelix is led to ask ‘What do you keep on saying what for?’ to which Anticlimax replies, ‘I say, sir, don’t you know what’s what, what?’ (Click on the image to enlarge.)

To pave the way for a magnificent joke a little later, Asterix’s invitation to Anticlimax is subtly and more specifically reworded: ‘viens chez moi’ becomes ‘Come and see round my house and garden’. The French authors poke fun at the English obsession with gardening at several points in Asterix in Britain, and the exchange we see here is the first example of this. Anticlimax replies, ‘A garden is a lovesome thing, God wot!’ to which Obelix’s rejoinder is ‘What’s wot, what?’ Of note here are the following points:

i) Godwottery – not a word in common use! – means excessively elaborate speech or writing, especially regarding gardens. Hence the use of ‘lovesome’, noted in the COD as adj. literary, and therefore not a word commonly used in everyday speech.

ii) God wot: ‘wot’ is an archaic form of ‘know’, so Anticlimax’s comment could be paraphrased as ‘God knows”.

iii) ‘What’s wot, what?’: an echo of Anticlimax’s ‘what’s what, what?’ in the third frame at the top of the page. This is a joke which works on both a phonological level, because it is an echo, and on a graphological level: Obelix could not possibly hear Anticlimax’s alternative spelling of ‘wot’.

It’s all very clever stuff, and certainly rewards the extra bit of investigation necessary to rootle out everything that’s going on here.

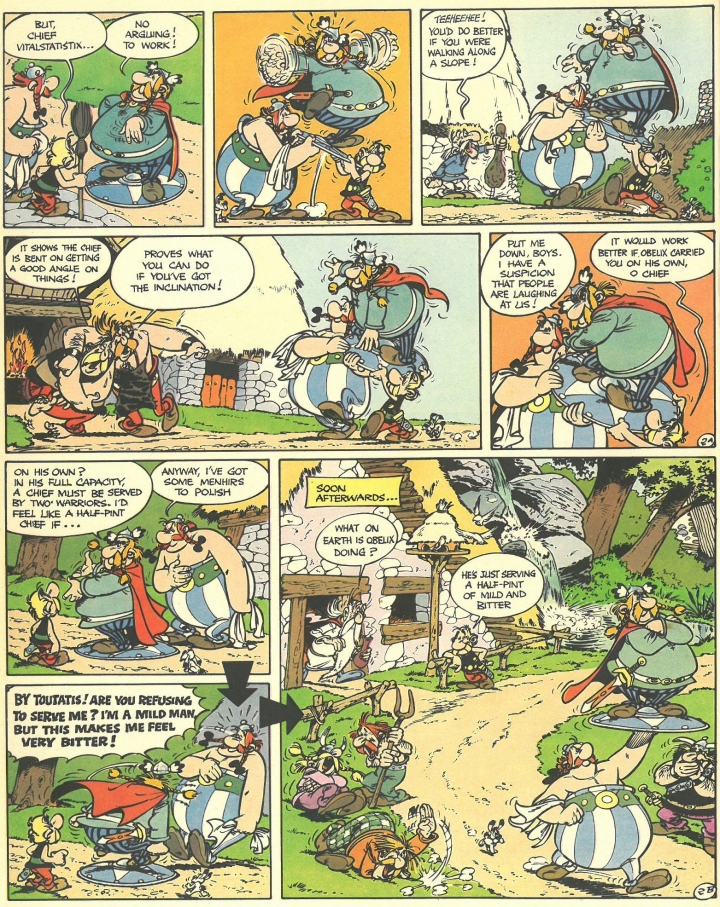

IV. The beer gag: Asterix in Switzerland

This joke is both an elaborate pun and a visual gag. It works slightly better in English because the translators got a little bit more mileage out of it.

In French, Abraracourcix/Vitalstatistix complains ‘J’aurais l’impression de n’être qu’un demi-chef si…’; Astérix picks up on the idea of ‘demi-chef’ for ‘Il est en train de servir un demi.’ This refers to a half-litre of beer, served under the metric system in France. (Click on the image to enlarge.)

In English, Vitalstatistix complains that with only one warrior to carry him, he feels like a ‘half-pint chief’. A sentence is added to his outburst in the next frame, ‘I’m a mild man but this makes me feel very bitter!’ which later allows Asterix to quip, ‘He’s just serving a half-pint of mild and bitter.’ (Click on the image to enlarge.)

The visual gag is of course Obelix holding the chief aloft on his shield as a waiter would carry a tray of drinks, the most elegant touch being the cloth draped over Obelix’s arm: he was going to use this cloth to polish his menhirs but now the cloth completes the picture of Obelix as a waiter. Vitalstatistix, the half-pint of mild and bitter, retains an expression of nobility befitting a Gaulish chief, even though his subjects are quite literally rolling on the floor laughing.

I love it. I love it all. I love it all now as much as I ever did.

Very good post. You must blog more about the other jokes. I had a hearty laugh reading ” he is serving a half pint of mild and bitter”, and it is the middle of the night here, mind you.

LikeLike

Thank you, I’m very glad you enjoyed it! I’m having trouble finding the time to write blog posts at the moment, but I will try to write more soon…

LikeLike

This is a great post! I’m a big fan of Asterix (in English 🙂 ) myself. It was also great to see Gericault’s painting discussed. One, he is again a favourite painter of mine; two, I once managed to be in the Asterix museum in Saarbrucken, where, among Goscinny’s original canvases of other classic and famous paintings, this one was there too. Really enjoyed reading.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much, and I’m very glad you enjoyed the post. I wrote this piece years ago, but it’s still one of my most popular posts: a tribute to the enduring popularity of Asterix! Must say in return how much I like your blog. It’s fantastic. I’m supposed to be studying, but I’d rather be looking at your work…

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike

Hi

I remember Derek Hockridge when I was a child. He was friendly with my father and I think they played squash together. I recall seeing him on Crown Court too. This was the mid 70s. Help! I feel so old

LikeLiked by 1 person

Can you help me? I have written a snail mail complimenting Ms Bell for the wonderful work she has done bringing Asterix comics to Enhlish speaking readers. For want of an address I am stymied and the letter stays in my drawer till date… Needless to say how much I appreciate your blog I came across online while surfing the net.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello Dr Vora,

I think Anthea Bell lives in Cambridge (UK), but beyond that I’m afraid I can’t help you with her address. If you send your letter c/o the publishers, I’m sure they will send it on. Good luck, and thank you for reading my blog!

LikeLike

I think the explanation for the second joke is incomplete. In the french, it’s as though the customer and melon merchant are replying to the conversation about umbrellas. There’s no need to invoke an “english businessman” stereotype – one conversation extols the virtues of umbrellas for keeping things off one’s head, while the other reacts, “what, this [bowler hat] is too expensive?” [in contrast to an umbrella]. In the english translation, the melon comment is now incongruous, but the “rather old fruit” can be interpreted both as a slur directed at the guy carrying an umbrella, or a slur *or* reply to the melon merchant, turning it into a triple-entendre.

LikeLike

Thank you for your comment, Darren. Yours is an interesting thought, but I think in the global context of the subject of this album – the visit to Britain – and in the localised context of Asterix’s question about native customs, the idea of poking fun at a stereotypical English businessman is a reading that still holds water. However, I do like the way that your interpretation, like mine, recognises the need to reconcile that which is depicted within the frame as a whole event, and not just a fragmented collection of happenings.

LikeLike

Hello, thank you for your article. If I remember correctly, in the next panel, Obelix says something like “look, this man is wearing a melon”, which is how the pun is delivered in French. I now wonder how it was translated, I should probably go find an English version. Thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh yes, you’re right! In the next panel, Obelix’s comment (in English) is ‘I say Asterix, I think this bridge is falling down’, but in the French, he does indeed comment on a Londoner wearing a bowler hat (‘Tu as vu, Astérix? Ce Londinien est coiffé d’un melon!’). In which case, I’m definitely sticking to my reading of the English businessman stereotype. And yet again, we see how Anthea Bell freely adapted the text when there was no way to make it work in English. Hats (or melons) off to her. Her passing is a sad loss to the world of translation.

LikeLike

This article is fascinating. The translations are so ingenious and creative. I’d like to add a comment for the The Godwottery joke. “A garden is a lovesome thing, God wot” is the first line of a 19th century poem by Thomas Edward Brown.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Clare. These translations just yield more and more all the time!

LikeLike

Thomas Edward Brown. 1830–1897

My Garden

A GARDEN is a lovesome thing, God wot!

Rose plot,

Fringed pool,

Fern’d grot—

The veriest school

Of peace; and yet the fool

Contends that God is not—

Not God! in gardens! when the eve is cool?

Nay, but I have a sign;

‘Tis very sure God walks in mine.

LikeLike

Thanks for this wonderful post! Exploring connections between languages is one of my passions, especially when it concerns idiomatic expressions, or even better, pun. I had a great time reading this!

One tiny detail: in France, “un demi” is 25 cl. It is (close to) a half-pint, to a half-liter (a half-liter would be a bit more than a pint). French people say “une pinte” when they want a half-liter. In Belgium (at least in some places) “un demi” is a half-liter (so kind of like a pint), though. This is maybe one of the rare circumstances where the French refer to the imperial system! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad you enjoyed the post, and many thanks for the clarification! xx

LikeLike

Thread necromancy here; I’ve long been a *huge* fan of Astérix and have almost every album (save the last four, it’s been a while since I’ve been to Europe) and several in about 8 different languages. This is a wonderful post about a wonderful subject and a pair of masterful translators.

I chuckled in “Astérix en Bretagne” where one sees souvenirs from previous adventures on the shelf, to wit: Astérix Légionnaire, Astérix chez les Goths, La Serpe d’Or, Astérix Gladiateur, and Astérix et Cléopatre.

“Il est en train de servir un demi” always made me laugh hard, the originals are pricless. Thanks for a great read!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! Glad you enjoyed the post x

LikeLiked by 1 person

My favourite translation is of Ideefixe to Dogmatix. Not only is the -ix prefix retained and the idea of stubbornness conveyed, but the translation adds a reference to the dog being a dog.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am French and my theory of where Idefix got his name is this: he first appeared in “Le tour de Gaule d’Astérix”, where Astérix and Obélix travel around Gaul. The dog is apparently a stray dog who sees them and follows them all the way around Gaul until they get back home and he finally jumps into Obélix’s arms. He followed them all this way, never giving up, you see. He was obstinate. In French we’d say it was his fixed idea, son idée fixe. Hence the name. It’s just a theory and I think most French people don’t know this possible explanation (or care) but I like to believe it’s correct. 😊

LikeLike

Hello! Back when I was reading Asterix in my teens in the 70s, in both English and French, Hodder Stoughton used to produce little tall pamphlets to help English school kids with the french idioms and cultural references. I asked Hodder a few years ago whether these still exist, but they denied any knowledge. Do you by any chance know if these survive anywhere? They were an amazing resource.

LikeLike

I don’t, I’m afraid – sorry!

LikeLike

I sick of you always going on about boars… I’m bored of you always going on about sickles. (or something along those lines and I don’t remember which book). Genius

LikeLike

Excellent work. Very good indeed. In the section on the beer gag, you write: “This refers to a half-litre of beer, served under the metric system in France.”

That should read: “This refers to a quarter-litre of beer, served under the metric system in France.” A ‘demi’ is half a full-size glass or half of half a litre.

LikeLike

Similarly, the original (French) Magic Roundabout was (apparently) somewhat dull, so when it migrated across the Channel it was completely re-written and re-voiced,by Eric Thompson (father of Emma) into the cult programme it became.

LikeLike

The Magic Roudabout wasn’t “dull” in the French version (in my recollection). It was quite funny and had a kind of craziness to it. Aimed at kids, yes, but very creative. And the characters were voiced by different actors. And the dog, Pollux, had an English accent. 🙂

Needless to say Astérix was never dull. 😊

LikeLike